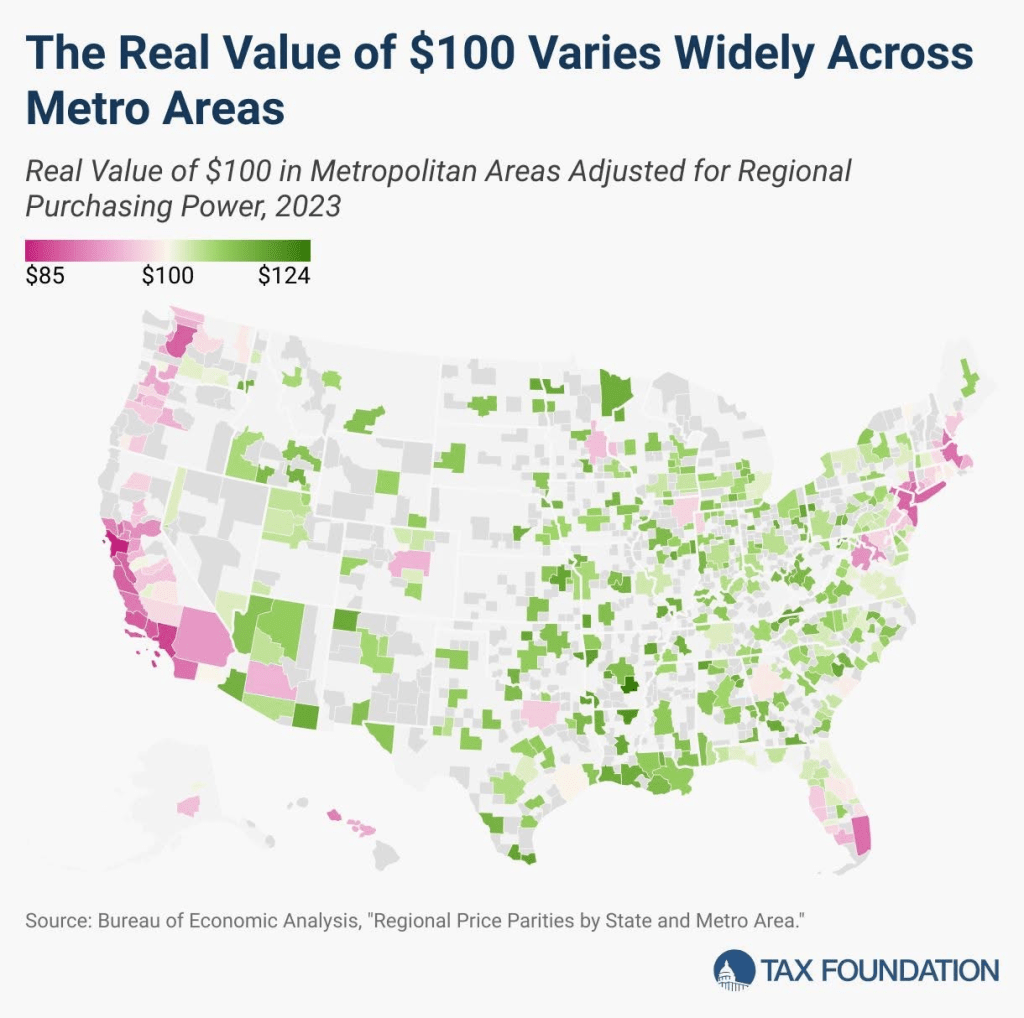

A recently published map from the Tax Foundation illustrates a reality many Kingsport residents intuitively understand but rarely see quantified so clearly: the real value of a dollar varies dramatically across the country—and Kingsport sits firmly on the favorable side of that divide.

Adjusted for regional purchasing power, $100 stretches meaningfully farther in much of Tennessee than in large coastal metros or even many fast-growing Sun Belt cities. Within Tennessee, Northeast Tennessee—and Kingsport in particular—stands out not merely as “cheaper,” but as a place where affordability aligns with stability, amenities, and quality of life.

That distinction matters.

In much of America, especially along the West Coast, the Mid-Atlantic Corridor, New England, and South Florida, $100 effectively buys about $85 worth of goods and services. Housing costs, insurance, utilities, and taxes quietly erode household budgets. Even middle-income families and retirees find themselves running faster just to stand still.

By contrast, in Kingsport—and in peer metros across Northeast Tennessee—the same $100 delivers closer to $117 in real purchasing power. That is not a marginal difference. Over a year, over a decade, or over a retirement, it becomes transformational.

But affordability alone is not the whole story, and this is where Kingsport differentiates itself from other low-cost markets nationally.

Some places are inexpensive because they are isolated, declining, or lacking in opportunity. Kingsport is none of those. It is a city with great access to healthcare anchored by a regional medical hub, strong public schools, a walkable Greenbelt system, and proximity to higher education, outdoor recreation, and a regional airport. It sits within a day’s drive of half the U.S. population, closer to Charlotte than Nashville, and at the gateway to the Southern Appalachians.

Within Tennessee, the contrast is becoming sharper. Middle Tennessee has seen rapid cost escalation. Nashville’s growth has been impressive, but it has come with housing prices, congestion, and service costs that increasingly resemble the metros many people were trying to escape. Memphis, Knoxville, Chattanooga, and Clarksville are not far behind.

Kingsport, by comparison, offers a rare balance: modest housing costs, manageable growth, and a community infrastructure built for everyday living rather than speculative expansion. For retirees, it means fixed incomes go further without sacrificing healthcare access or cultural life. For working families, it means the possibility of a single-income household, a trailing spouse, or simply breathing room in the monthly budget. For professionals working remotely, it means national-level salaries paired with local-level expenses.

Nationally, policymakers often frame affordability as a tradeoff—low cost versus high opportunity. Kingsport quietly disproves that framing. Its economy benefits not only from wages, but from “income-light, asset-heavy” households—retirees, investors, and entrepreneurs—whose spending supports local businesses, nonprofits, and civic institutions without overwhelming local infrastructure.

The map from the Tax Foundation is not just an academic exercise. It is a reminder that value still exists in America—and that it is increasingly concentrated in places that have chosen balance over boom-and-bust growth.

Kingsport’s challenge now is not to become something it is not, but to recognize and protect what it already is: a city where dollars stretch, quality of life remains high, and prosperity is measured not just in growth rates, but in livability.

In an era when so many communities are priced out of their own success, that may be Kingsport’s greatest competitive advantage.

Leave a reply to larrypennington Cancel reply