The South. Just reading those words probably evokes imagery. For natives, it might be sweet tea, biscuits, and “home sweet home to me.” For others, it might be The Beverly Hillbillies, The Dukes of Hazzard, or The Andy Griffith Show.

I follow a TikTok account of a former New Yorker now living in Charleston. She shares her day-to-day discoveries of Southern culture and colloquialisms—often framed as, “Here’s what I assumed before I lived here.” Bottom line: she’s completely bought in, and she tries to explain to people outside the region why it feels like a welcome breath of fresh air.

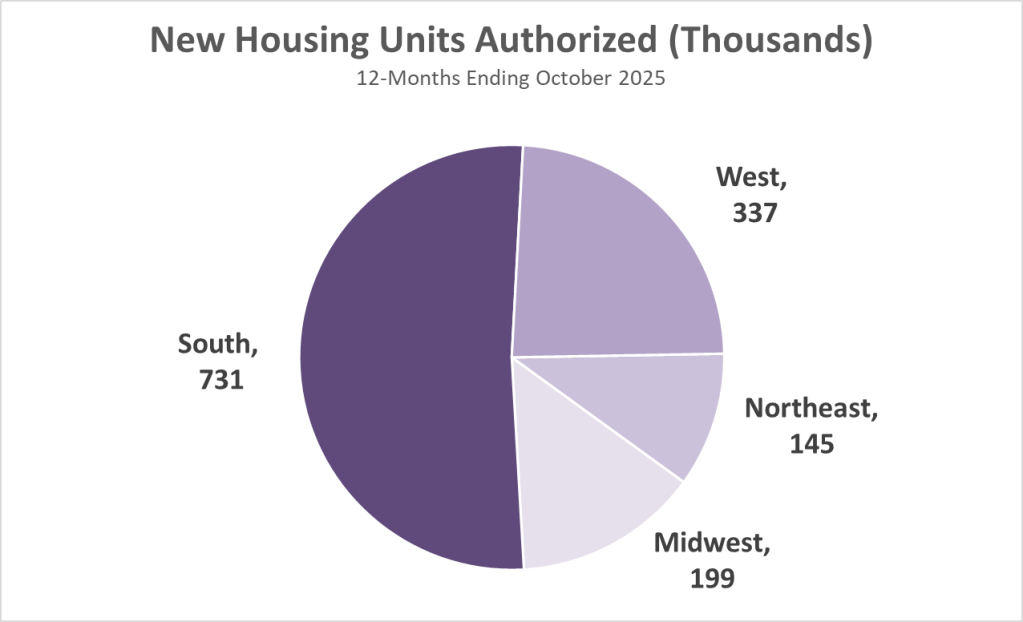

The Census Bureau’s residential construction report is one of the most useful economic indicators we have. I read the latest one this week, and the same thing jumped out again: the South is still outbuilding the rest of the country combined in single-family housing.

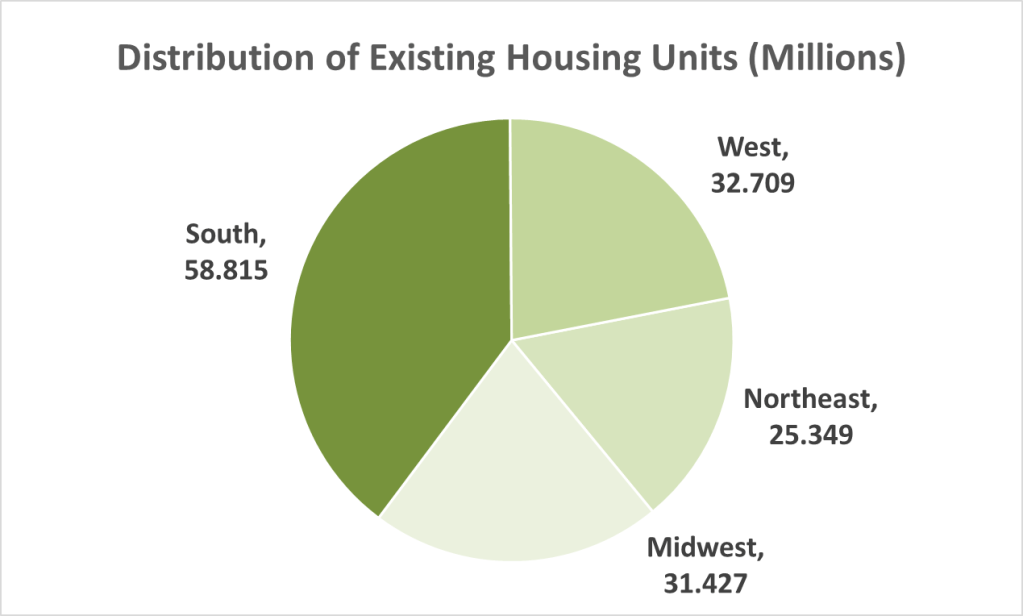

And the South is adding more units to an already larger base.

And yet the South is often dismissed. Critics point to higher poverty rates, lower educational attainment, and our seemingly relentless habit of labeling people as red, blue, or purple. The subtext can sound like, “Who would want to live here?” But those points miss important nuance.

Take poverty. The official poverty measure has limits, and it does not fully capture differences in local costs—especially housing. Hardship is real everywhere; the question is how far a paycheck actually goes.

Or take educational attainment. Counting degrees is easy; measuring financial outcomes is harder. Degrees can open doors, but they can also come with a long tail of student-loan debt. Meanwhile, many trades—electricians, plumbers, HVAC techs—offer strong, stable earnings with little or no college debt. I am not knocking higher education; I am saying that “more degrees” does not automatically equal “more prosperity.”

The lived reality—and a lot of the data—tell a more complicated story. The South continues to perform well on basics that matter to families: a realistic path to homeownership, attainable rents, and the ability for working households to earn a living.

I believe people vote with their feet, and a home—the biggest investment most families make—reveals what they value and what they can afford. And more families are choosing The South.

Which brings us to the heart of the affordability debate. It often circles the same culprits—investors, landlords, and developers—but the underlying math has not changed. Supply and demand still rule the day. Prices rise fastest when demand is strong, and inventory is tight—and inventory stays tight when we are not building enough homes in the places people want to live.

That is why the South matters so much in the current cycle. In October 2025, the nation authorized 1.412 million housing units (annualized), and the South accounted for 731,000 of them—just over half of the U.S. total. From September to October 2025, the South fell (-3.3%). If the South is America’s supply engine, those are signals worth watching.

Multiple credible estimates put the U.S. short millions of homes, so we start each demand upswing with too little slack.

Post-2008 recession, tighter credit and heightened risk controls changed the economics for homebuilders (especially smaller builders), while land-use constraints in many markets continued to accumulate. When demand rises, constrained supply shows up as higher prices.

Faced with rising rents, some places turn to rent control, while others float broader ideas about social housing. New York City has become a high-profile test case for competing approaches.

For now, these remain more like expressed viewpoints than settled policy. But well-intended programs almost always carry unintended consequences.

That brings us to the latest political move in the national debate. The President has said he is taking steps to bar large institutional investors from buying additional single-family homes and has urged Congress to codify the idea. Even if that policy advances, large institutional investors own a relatively small share of the nation’s single-family housing stock overall, though their presence can be more concentrated in certain Sun Belt metros. Restricting corporate buyers might help at the margin in a handful of overheated markets, but it cannot substitute for building enough homes to meet demand.

So, what is the solution? Make it feasible to build—while setting clear, predictable guardrails. That means sufficient zoning capacity, faster and more transparent approvals, and consistent standards that builders and neighbors can plan around, paired with targeted tenant protections where they are most needed. Preserving affordability will depend less on arguments about ownership or rent setting and more on whether communities allow enough homes to be built, with infrastructure timed to growth instead of forever playing catch-up.

For as long as I can remember, Kingsport has aimed to be “developer-friendly”—not as a giveaway, but as a discipline: an attentive city staff, committed boards and commissions, creative problem-solving, and a streamlined review and permitting process. That approach has helped keep housing options relatively attainable for both long-time residents and newcomers.

But we cannot take our eye off the ball. If we want affordability to remain a strength, we must continue to expand the supply—new homes in new neighborhoods, infill on vacant and underutilized parcels, rehabilitation of older homes with good bones, and thoughtful density downtown and along corridors where infrastructure already exists.

As my grandmother used to say, “All things in moderation.” We do not need to put all our eggs in one basket. We need a diversified housing portfolio—new construction, infill, rehabs, and a mix of housing types—that meets the needs of people at every age and income level. And Kingsport has—and is—doing that.

Leave a comment