Recently, we published an article titled “Safer by Design, Not by Statistics” that shows why Tennessee’s crime rate isn’t an apples-to-apples comparison with other places—and how it’s often misused to suggest we’re less safe than we really are. You can read it at KingsportSpirit.com.

Another misleading statistic is the poverty rate.

Appalachia is “poorer” than inner-city New York or Los Angeles. That’s what the federal rulebook says. But is it? There’s a fundamental flaw in the data.

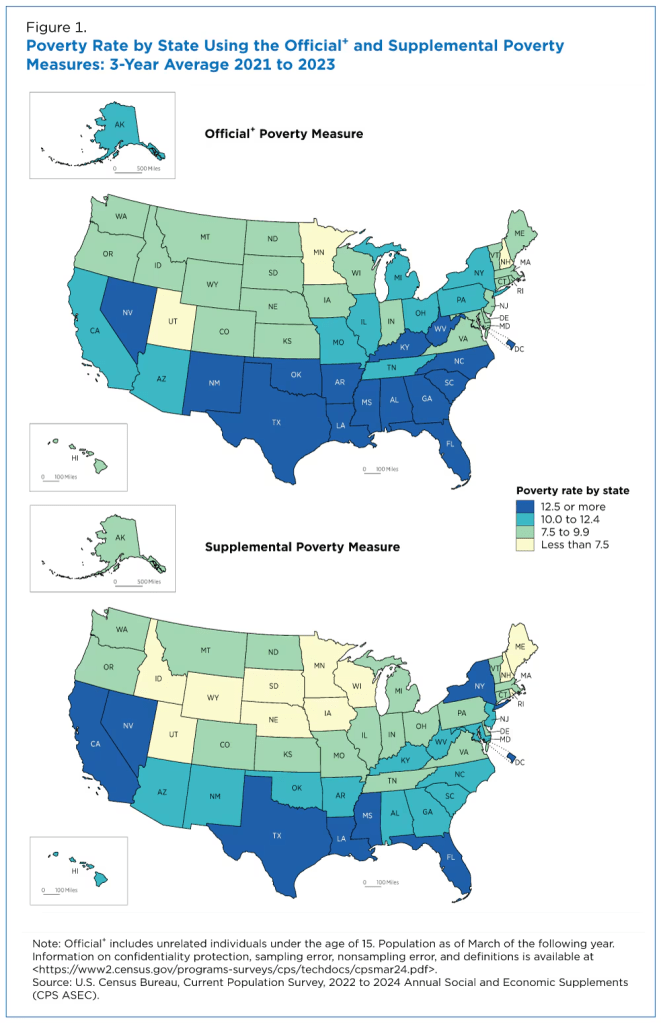

The Official Poverty Measure (OPM) is built on a 1960s food-budget formula that adjusts for inflation but not for cost of living. It treats a dollar in Appalachia the same as a dollar in Manhattan or Beverly Hills—flattening the map on paper while hiding the real difference families feel each month. Because incomes are lower here, more Appalachian families fall below that line.

The result? A national narrative that Appalachia is poorer than the rest of the country. After six decades, that story starts to feel like an identity.

That label shapes outside perception and risks fostering generational dependence, even where families have long managed to make ends meet. But the constant drumbeat carries another cost: when people are told they’re poor often enough, they can start to believe it. Hope erodes into resignation, resignation into despair—and despair can fuel destructive cycles like addiction. It’s a sobering reminder that statistics aren’t just numbers; they shape how people see themselves and their future.

Don’t get me wrong, there is real poverty everywhere and we shouldn’t sugarcoat it. We all have neighbors who need help with housing, mental health, addiction, and food security. We should fight poverty with programs that work. But we should also retire a 60-year-old story that paints all of Appalachia with one broad, negative brush.

That’s why many locals bristled at being rebranded the “Appalachian Highlands.” Outsiders may see the name as a positive, but to those who have lived under the shadow of poverty stereotypes, it felt like doubling down. When you say Appalachia, locals don’t hear “heritage” or “mountains”—they hear hillbillies and outhouses. For decades, Hollywood reinforced that caricature. The Beverly Hillbillies told America that when a poor Appalachian struck oil, the dream was to “load up the truck and move to Beverly Hills.” The joke, of course, was that rural people weren’t ready for the sophistication of city life. But today, the script has flipped. Families from crowded, costly metros are the ones “loading up the truck” and moving to Tennessee—drawn by affordability, breathing room, and a quality of life that outshines the caricatures.

I was talking with a colleague recently about our families’ resilience during the Depression. Back then, they didn’t wait for Washington to solve things. They grew their own food, they bartered in place of cash, and they were largely unbanked. Many households weathered the storm because they were rooted in skills and networks that didn’t show up in any government statistic. As the old Alabama song put it, “Somebody told us Wall Street fell.” For much of Appalachia, that collapse felt far away because daily life ran on a different system—neighbors, gardens, and grit. That same resourcefulness still shapes our communities today, even if official labels can’t capture it.

Look through a better lens and the picture shifts.

The Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) adjusts for housing and other real costs. Under SPM logic, poverty rises in high-cost metros, where rent, insurance, and childcare devour paychecks. It falls in lower-cost places like Appalachia, where those basics are cheaper. But SPM is limited to the state-level and is only updated every three years. That’s a serious gap.

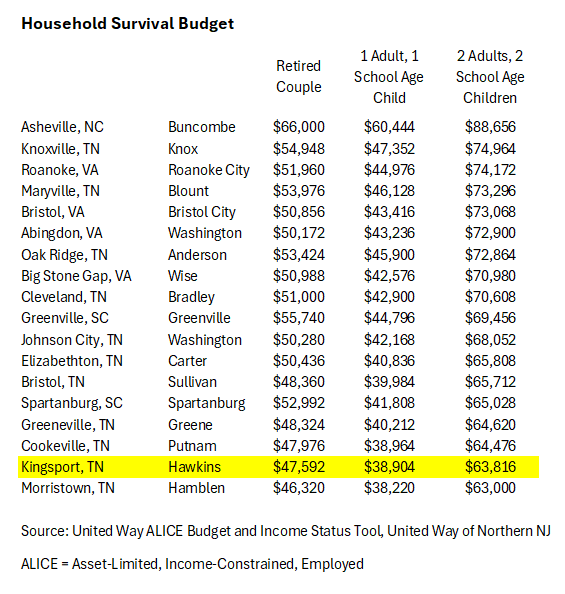

The clearest lens is United Way’s ALICE (Asset-Limited, Income-Constrained, Employed) framework, which tells a very different story. The official poverty measure (OPM) makes Kingsport (20.8%) look poorer than New York City (18.2%) or Los Angeles (16.5%). But ALICE measures what it actually takes to get by—and in Kingsport, the survival budget is much less than what families need in those big metros. A retired couple here can live modestly on $48,000 a year, a single parent with a school-age child on $39,900, or a family of four with two school-age children on $64,000. The same circumstances in Queens County, New York, require $78,000, $72,000, and $110,000, respectively. In this light, Kingsport isn’t “poorer” but more affordable—a place where lower wages stretch further, while in high-cost metros even middle-income households struggle to cover basics. ALICE is updated every two years with a consistent national methodology but published state by state, which ensures fair comparisons but means data only exists where United Ways participate—and California is not among them.

These measures matter. When policymakers skim the old, unadjusted rates, Appalachian towns can look worse off than big cities that “feel” far more expensive. That misread shapes how resources flow, how employers and recruits judge our communities, and even how we see ourselves: They keep telling us we’re poor–so we start to believe it.” Yet measured against actual costs, many Appalachian families enjoy more real purchasing power than peers in zip codes that only appear wealthy on paper.

The stigma problem goes further. Free school meals are essential, but when entire schools qualify under federal rules, “free lunch” no longer maps neatly to household hardship. Still, those percentages get used as a poverty proxy, branding schools unfairly. The same happens with “economically disadvantaged.” The term helps direct funding, but it also leaves parents, realtors, and even students themselves with the impression of failure—especially in affordable communities where the numbers don’t reflect daily resilience.

And here’s where well-intended help can backfire. In their book When Helping Hurts, Steve Corbett and Brian Fikkert warn that charity—if delivered poorly—can unintentionally reinforce a message of brokenness rather than dignity. Giving without context can disempower the very people it aims to lift up, replacing resilience with dependency. In Appalachia, decades of well-meant programs sometimes blurred the line between relief and identity. Aid is vital in moments of crisis, but when it becomes the headline of who we are, it feeds the very stigma we’re trying to erase.

So what should we do?

First, fix the scorecard. Lead with cost-adjusted measures like SPM. Show families what local budgets really look like: rent, insurance, utilities, transportation, and childcare.

Second, pair “need” with “proof.” If we publish participation or disadvantage rates, put them beside achievement data: early literacy, math growth, dual-enrollment credits, arts and athletics, apprenticeships. Use strength-based language and explain why the numbers look the way they do. Kingsport City Schools does a great job with this.

Third, tell the story families actually live. Appalachia’s advantage isn’t a slogan; it’s a spreadsheet. Lower monthly costs, shorter commutes, and realistic paths to homeownership give families breathing room—margin for savings, sports fees, music lessons, or a small emergency. That’s why people move here and exhale. It’s why official poverty can say one thing while daily life says another.

Take Kingsport. Measured fairly—and told honestly—it shows what many Appalachian towns prove every day: more affordable, more attainable, and more resilient than places that only appear well off.

As a co-worker once told me: “I live on the family farm debt-free—no mortgage. I get my water from a well, dispose of it in a septic tank, and I have high-speed internet. They compare me to people with 30-year mortgages and sky-high utilities. Now who’s poor?”

If you think about it, that sounds almost like the lyrics to Tennessee’s official state song: Ain’t no smoggy smoke on Rocky Top, ain’t no telephone bills. And in another way, it flips the old script of The Beverly Hillbillies. They once sang, “California is the place you ought to be.” Today, it’s Californians who are loading up the truck and moving to Tennessee.

Appalachia was built on fiercely independent, self-sufficient, and resourceful people. Well-intended programs, over time, have too often dulled that identity. Now it’s time to reclaim it.

Rocky Top, you’ll always be home sweet home to me.

Leave a comment