What IRS migration data says about Northeast Tennessee’s income inflow

It’s tax season, and we’re all thinking about federal income taxes. But a lot of Americans are also thinking about state income tax, and some even pay a local income tax.

Tennessee is the only centrally located state in the Eastern U.S. that doesn’t levy a state income tax—and local income tax is off the table here, too.

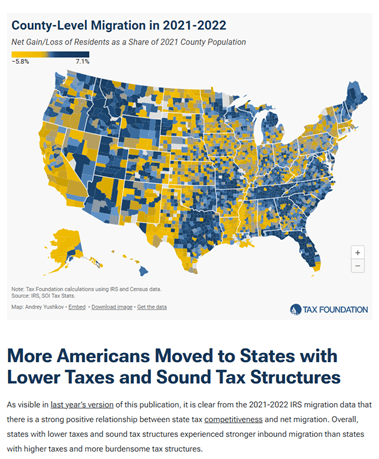

That policy reality shows up in the IRS numbers as an influx of AGI (adjusted gross income) reported on tax returns. The latest available IRS migration data is 2021–2022.

Look at how uniformly Tennessee shows migration. Almost every county—from the Great Smoky Mountains to the Mississippi River, and from the big bend of the Tennessee River to the Cumberland border with Kentucky—shows a similar story.

And here’s the bigger geographic reality: Northeast Tennessee sits right on a regional transition line. Just beyond our border, many rural Appalachian counties have been working against long-running headwinds—out-migration, aging populations, and limited job diversity. Drive north on U.S. 23 from Kingsport, and for roughly 300 miles, you don’t pass through a county showing positive population growth until you reach the Columbus, Ohio, metro.

Why does that matter? Because over time, population decline can translate into a smaller economic base—fewer workers, fewer customers, and less capacity to sustain the services that keep a community strong.

But unchecked growth isn’t desirable either.

The sweet spot is about 5%–10% per decade. Sullivan County is growing a little less than 2%—good, but not great. The real stress shows up in places like Wilson County, Tennessee (I-40 east of Nashville), which is growing at roughly 31% per decade—about three times a sustainable rate.

Even with modest growth, Sullivan County still saw a one-year gain of more than $100 million in income from out-of-state residents moving in during 2021–2022.

That’s one year.

Washington County (TN) saw $150 million. In fact, every county in Northeast Tennessee posted a significantly positive AGI gain from out-of-state migration: Greene ($55 million), Carter ($47 million), Hawkins ($41 million), Johnson ($29 million), Unicoi ($11 million), and Hancock ($4 million). Further down I-81, Hamblen added $35 million, and Jefferson added $52 million.

At the same time, the IRS data shows that some nearby counties to our north and west posted net AGI outflows during the same period—Scott (-$1 million), Wise (-$3 million), and Pike (-$2 million).

That’s not a value judgment on those communities; they’re our friends, family, and neighbors. It’s simply a reflection of broader economic geography—and the reality that regions compete for people and paychecks, often from very different starting conditions.

Compounded over time, the IRS’s reported influx (or outflow) of income is a strong signal. It’s not just a demographic storyline—it’s a balance sheet.

Counties that consistently lose people often lose wage earners, future taxpayers, and the customer base that keeps schools strong, small businesses healthy, and public services affordable.

Meanwhile, Northeast Tennessee is adding purchasing power—new households with paychecks, pensions, and investment earnings that translate into home purchases, local spending, civic involvement, and charitable capacity.

The strategic question isn’t “growth at all costs.” It’s whether we manage this moment well. Sullivan County’s modest growth rate gives us something faster-growing places don’t have: time to be deliberate—expanding housing supply responsibly, keeping infrastructure ahead of demand, strengthening workforce pipelines, and protecting the character that drew people here in the first place.

The economic map is already shifting around us. Our job is to recognize the signal early and make steady choices that keep this region strong—quietly, sustainably, and for the long haul.

Leave a comment