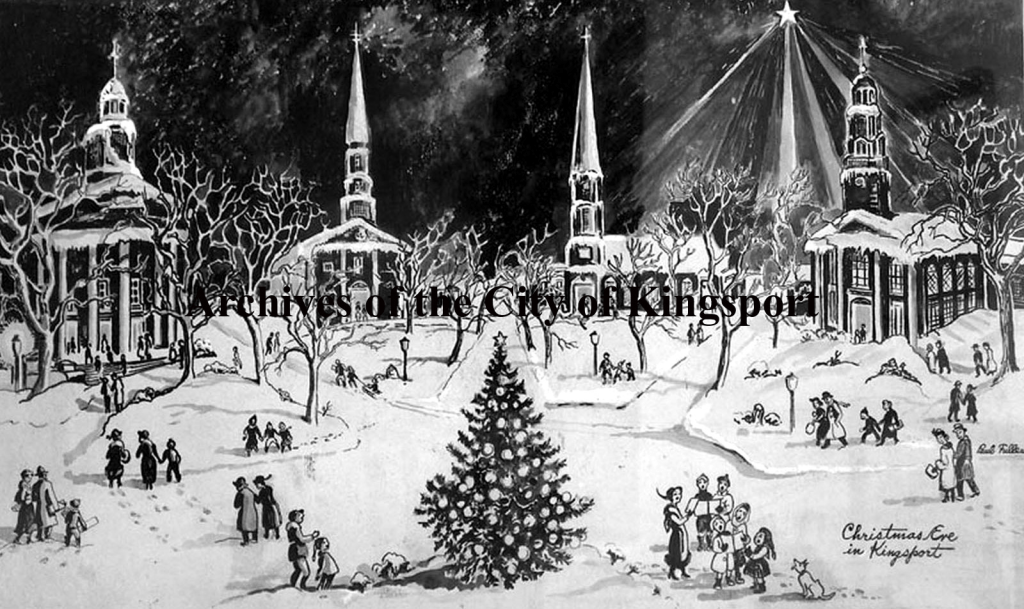

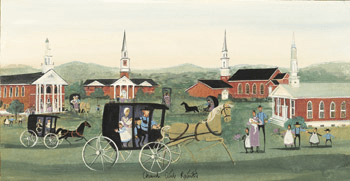

There’s just something about town squares. They are the settings of Hallmark movies and Christmas cards—the places where parades pass, lights are lit, and communities recognize themselves. They evoke warm memories of home, family, faith, and belonging. A true town square is not just a location; it is an emotional center, a shared reference point that anchors a community’s identity.

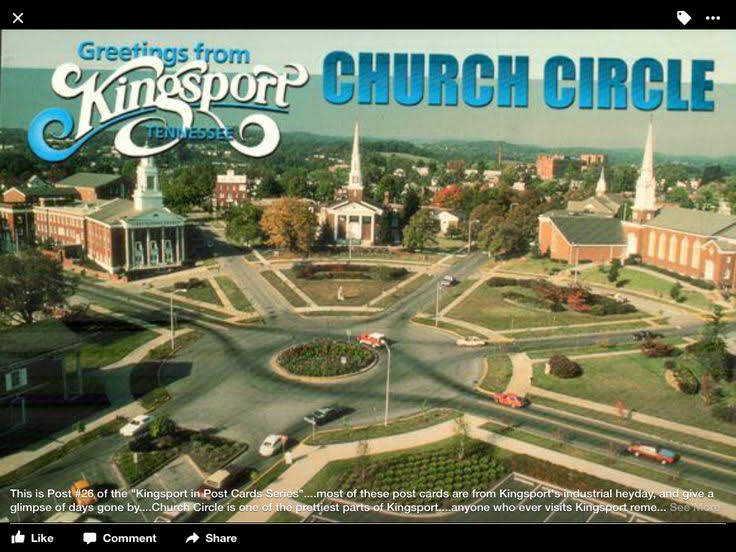

Church Circle is Kingsport’s town square.

It has filled that role for more than a century, even as the forces around it have changed dramatically. To understand why Church Circle matters—and why its survival is remarkable—it helps to understand the era in which Kingsport itself was born.

When Kingsport was incorporated in 1917, American cities functioned very differently than they do today. Communities were organized around passenger rail, streetcars, and pedestrian movement. Automobiles existed, but they were still relatively rare, expensive, and unproven. No town planner of the era—no matter how skilled—could have predicted how completely the automobile would reshape daily life, commerce, and city form. Early 20th-century planning emphasized walkability, proximity, and civic presence, not traffic engineering as it would later be defined.

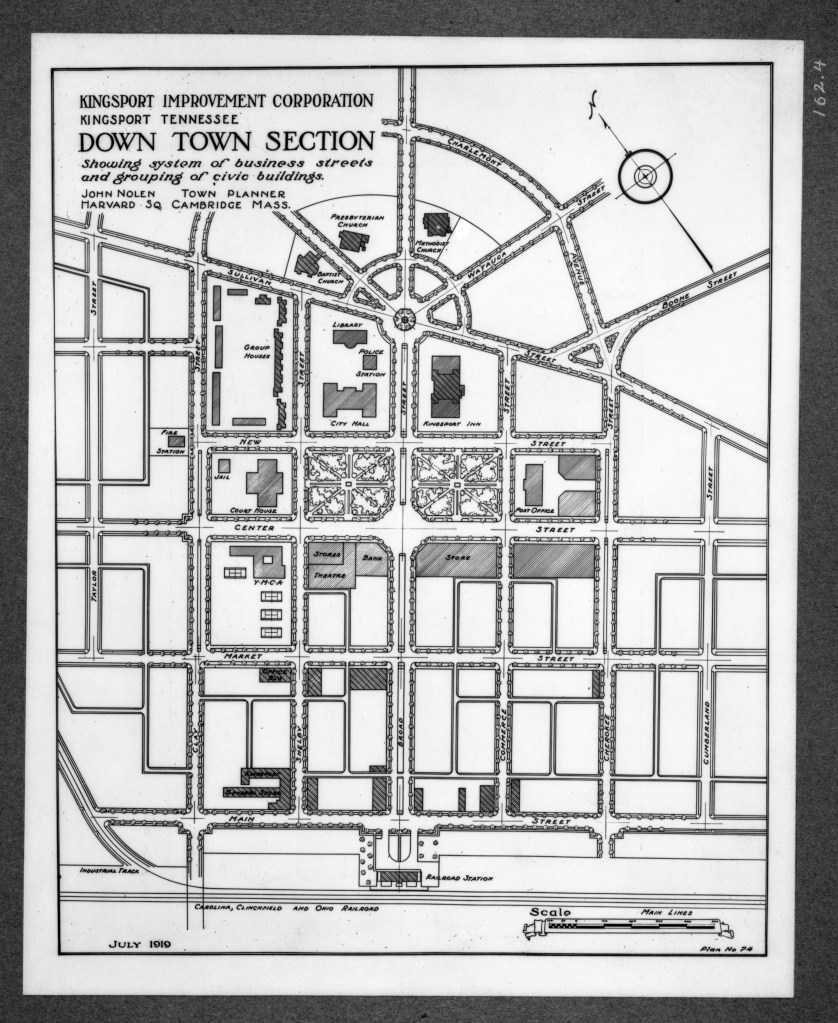

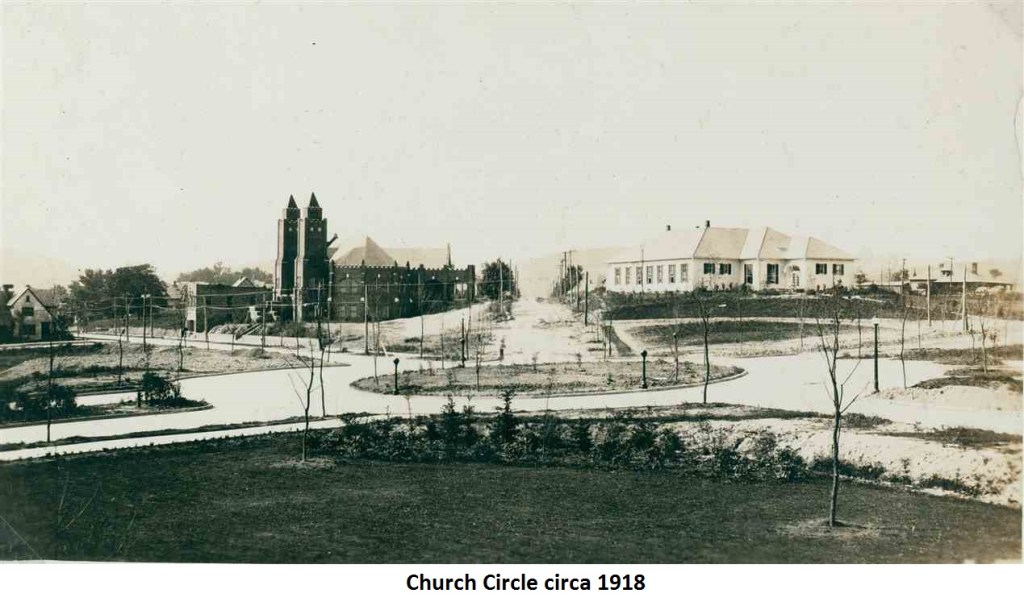

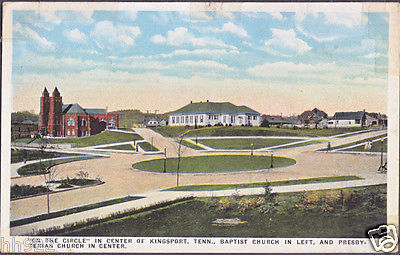

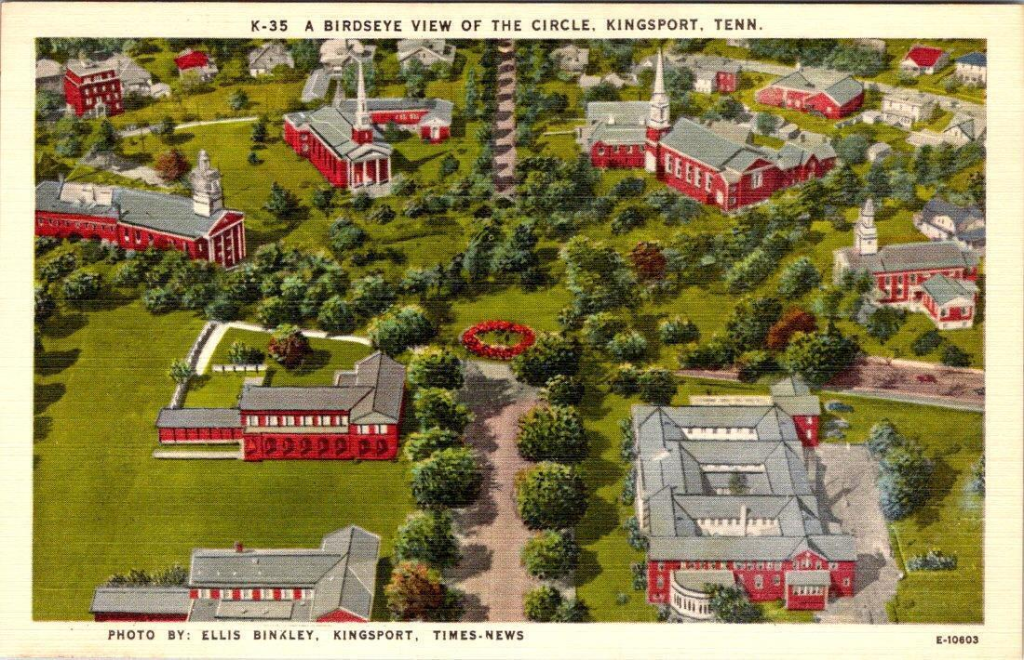

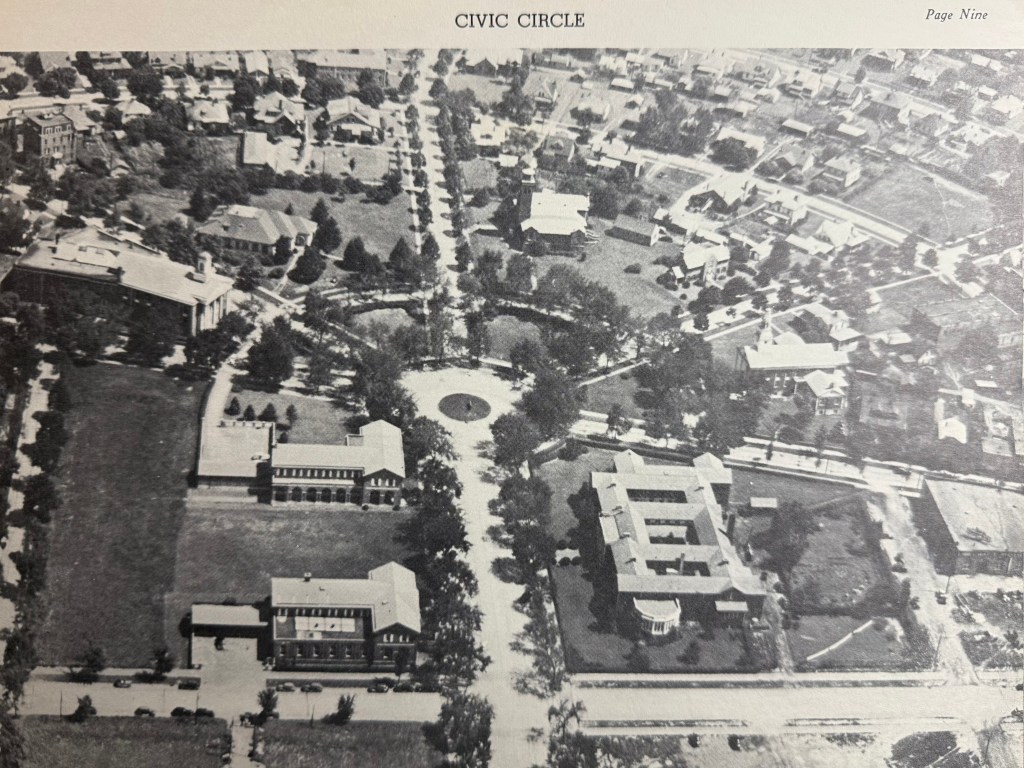

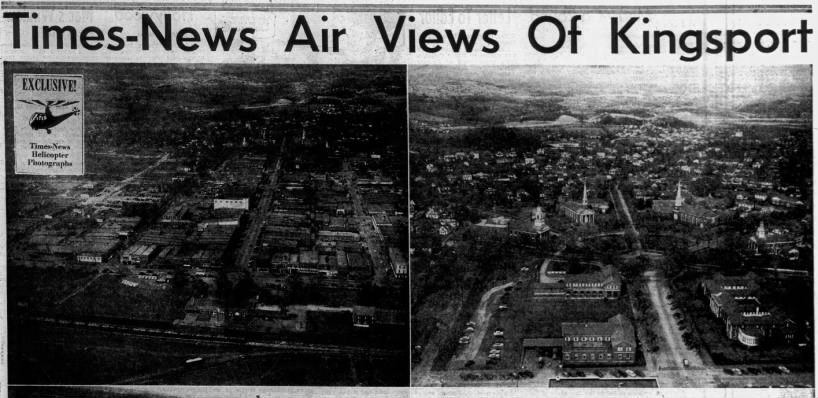

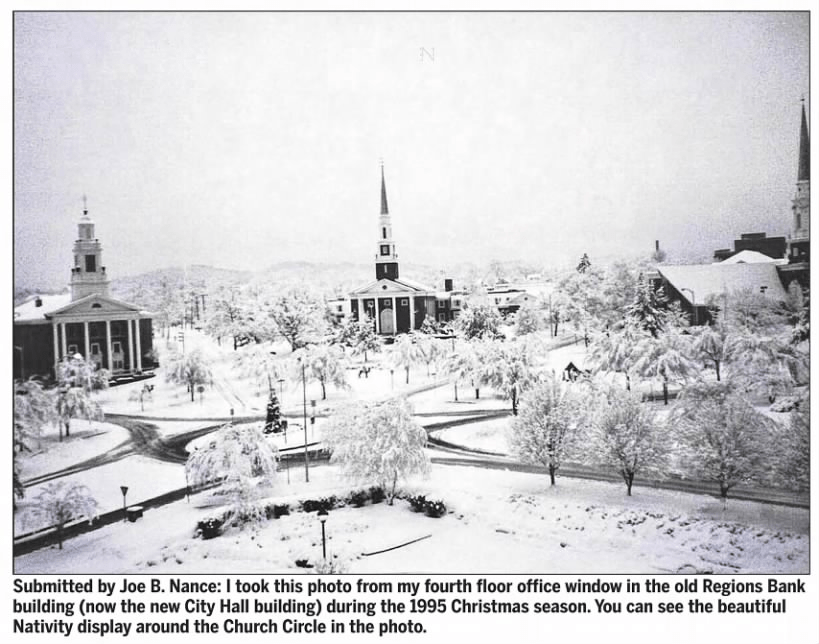

Kingsport’s 1919 master plan, prepared by railroad engineer William Dunlap and refined by nationally recognized planner John Nolen, reflected those assumptions. The spoke-and-wheel layout placed Broad Street at the center as the city’s primary civic axis, with streets radiating outward and converging at Church Circle. Streets named Holston, Watauga, and Sullivan tied the plan to the region’s geography. Church Circle was literally the hub of Kingsport.

Growth came quickly. From a presumed population near zero at incorporation, Kingsport reached approximately 5,700 residents by 1920, nearly 12,000 by 1930, and more than 14,000 by 1940. Then came World War II. The opening of the Holston Ordnance Works in 1943 pushed the city into an entirely new scale of activity, bringing thousands of workers into the region on tightly compressed shift schedules. Traffic surged in predictable waves. Former Kingsport mayor Hunter Wright, recalling that era, said that during shift change you could walk on the rooftops of cars from the Holston gate to downtown. Literal or not, the comment captured a deeper truth: Kingsport’s streets were never designed for that volume.

By 1950, the city’s population approached 20,000, climbing to 26,000 by 1960 and nearly 32,000 by 1970. As in cities across America, the automobile moved rapidly from novelty to necessity. What is often overlooked, however, is just how concentrated that impact was in Kingsport.

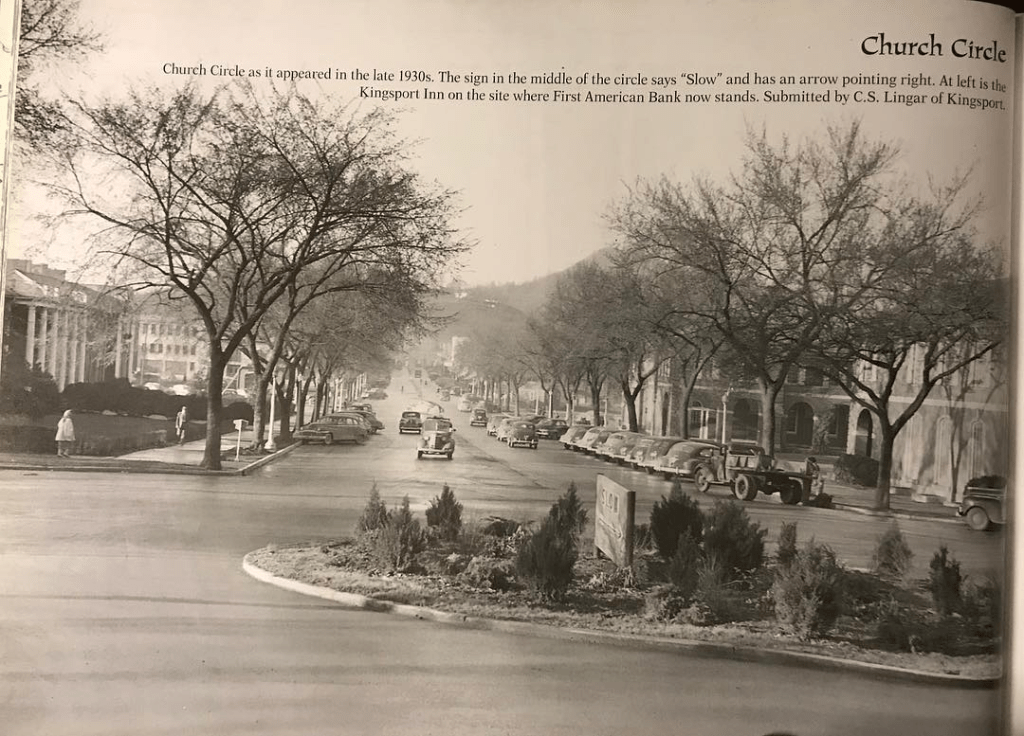

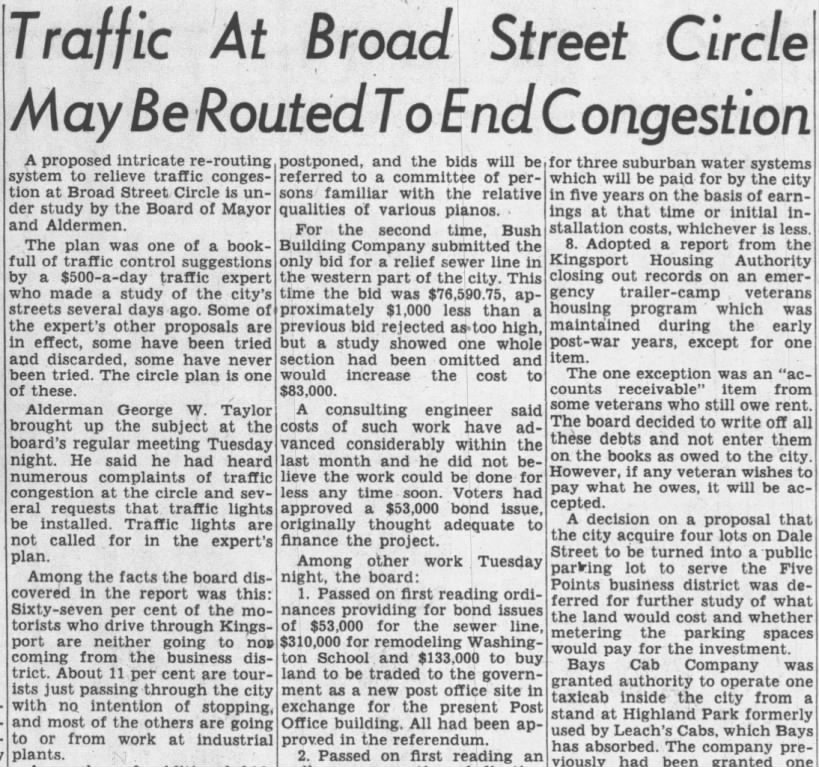

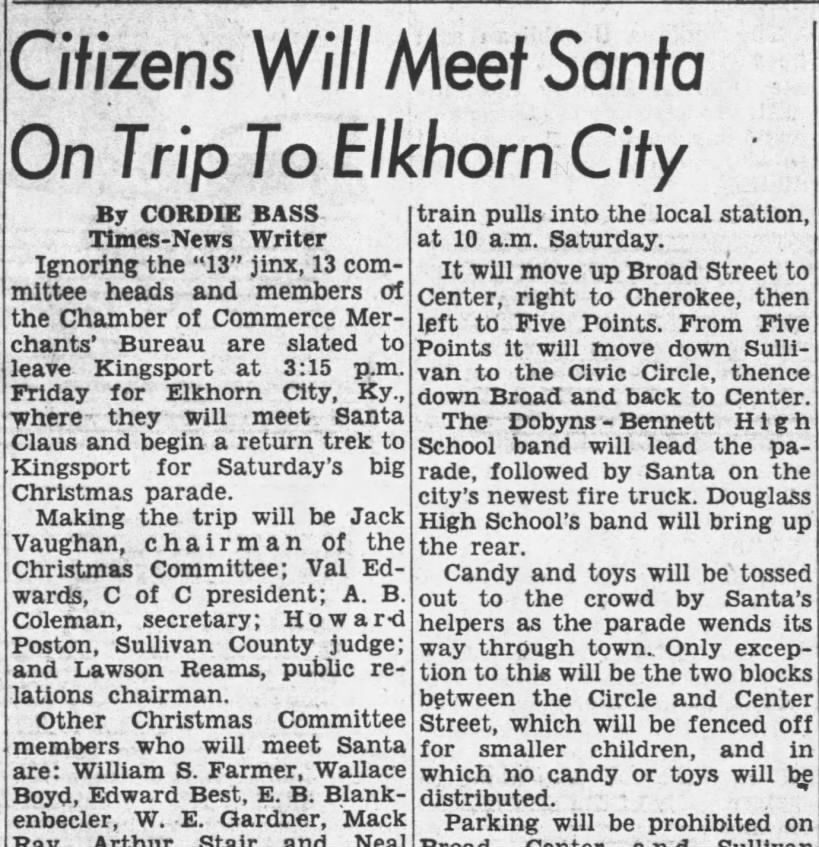

For nearly a quarter century—nearly all regional through-traffic passed directly through downtown on Sullivan Street. U.S. 11W and U.S. 23 ran straight through Church Circle. Every truck moving between Bristol and Rogersville, or Johnson City and Gate City. Every regional traveler. Every commuter. There were no limited-access roads, no freeways, and no true bypasses.

Officials attempted incremental relief. West Center Street was extended to West Sullivan Street in 1939, an early acknowledgment that downtown streets were beginning to strain. But this was a pressure release, not a solution. It did not change the fundamental reality. It took almost another quarter century before Lynn Garden Drive would be extended to Center Street and the new “superhighway”, Stone Drive, would open for traffic.

Sullivan Street was the highway.

Let that sink in.

That reality placed extraordinary pressure on Church Circle. What had been conceived as a civic anchor increasingly functioned as a choke point for regional mobility. This was not a failure of planning, but the unavoidable outcome of a personal car revolution no one could have fully anticipated.

The early 1960s marked a decisive inflection point for Kingsport and for me. I was born in 1961, so it’s my frame of reference. But more importantly, it was the year Kingsport’s center of gravity visibly began to shift.

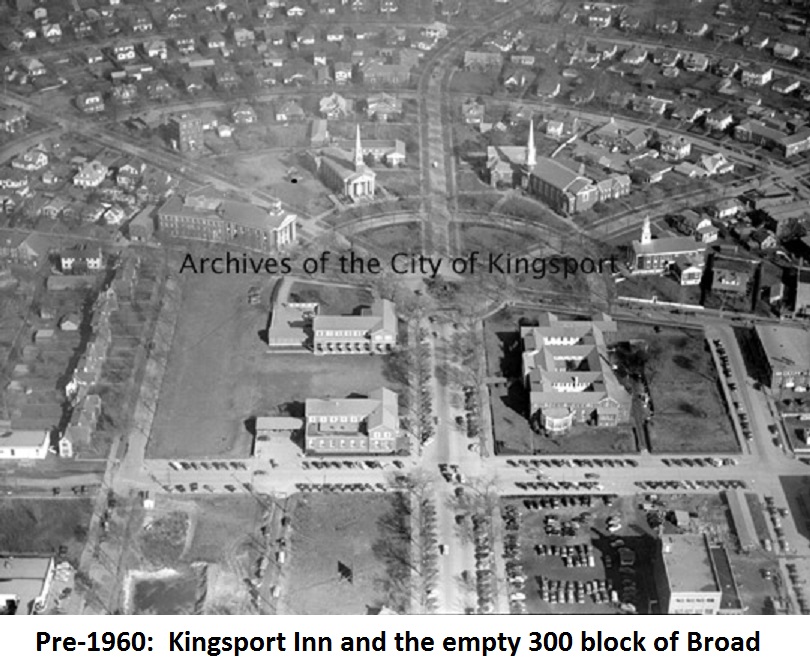

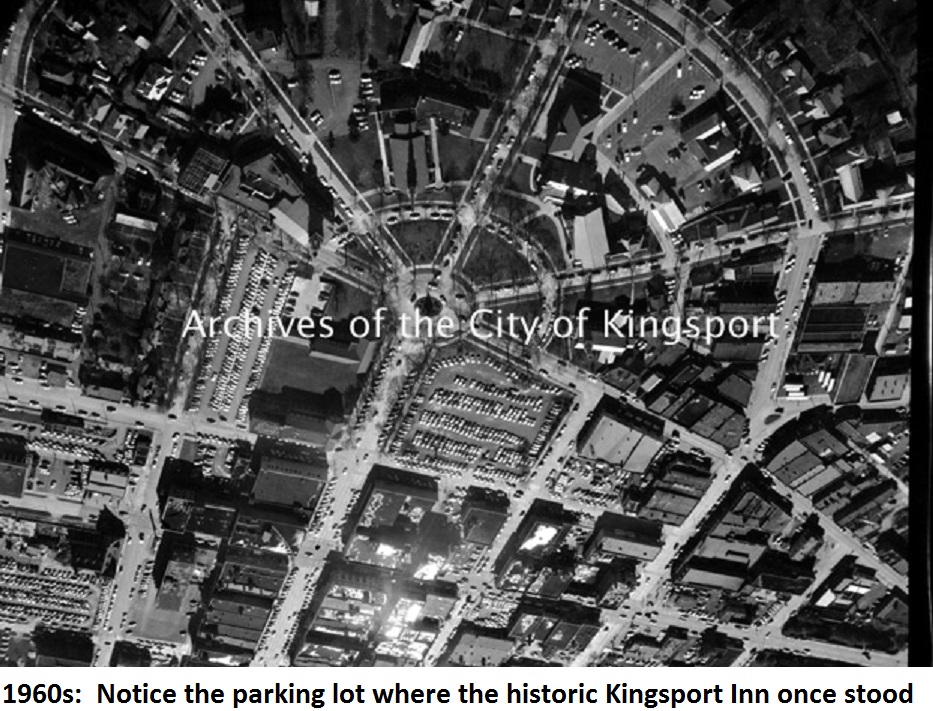

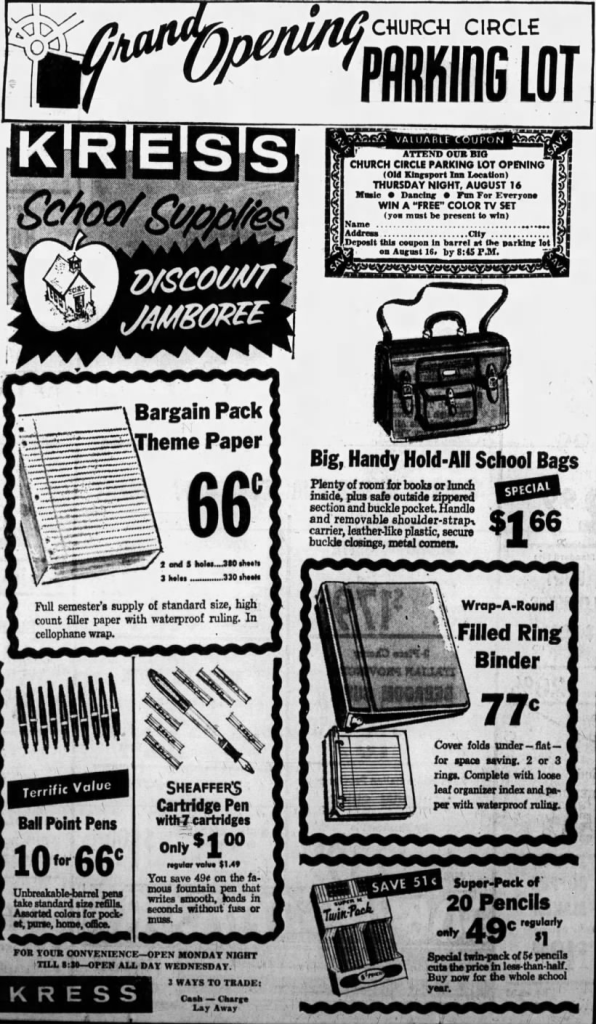

In 1961, the Kingsport Inn closed, ending an era when downtown hotels were social anchors and symbols of civic stature. Almost simultaneously, Holiday Inn opened on Lynn Garden Drive, with Howard Johnson’s on Stone Drive not far behind—clear signals that the future of travel and hospitality now belonged to the automobile. Two years later, Sears relocated to Eastman Road, underscoring that major retail no longer required a downtown address.

Auto dealerships followed the traffic. Also beginning in 1961, Latimer-Looney Chevrolet moved from 713 East Sullivan Street to 1220 East Stone Drive, setting off a cascade as Chrysler-Plymouth brand left Mills Motors at 223 Commerce Street for Alley’s at 939 East Stone Drive, Craft Motors became Anderson Ford and relocated from 212 East Sullivan to 425 Lynn Garden Drive, Lincoln-Mercury left Tom Yancey’s at 321 Revere Street for Kingsport Motors at 861 East Stone Drive, and Barnes Motors (212 Clay Street) became Don Hill Pontiac, moving to 2523 East Stone Drive, and Cox Oldsmobile moved from 318 Cumberland Street to 415 West Stone Drive. Together, they drained daily activity from the historic core.

Retail soon followed—and it began earlier than many remember. In 1960, the opening of Green Acres Shopping Center marked one of Kingsport’s first decisive moves toward automobile-oriented retail. With ample parking and easy access, it previewed a future in which convenience and visibility increasingly outweighed proximity to Church Circle. Green Acres did not replace downtown overnight, but it quietly changed expectations.

That shift accelerated quickly. Parkway Plaza opened on Lynn Garden Drive at West Stone Drive, anchoring a new commercial corridor. In 1969, the Kingsport Mall was announced, taking Montgomery Ward from downtown. By the mid-1970s, Fort Henry Mall would claim the remaining anchors—JCPenney, Parks-Belk, and Miller’s—completing a migration that permanently reshaped how Kingsport shopped and gathered.

Fast food and roadside dining followed close behind. Although the original Pal’s had been a downtown staple at 327 Revere Street since 1956, McDonald’s opened its first Kingsport location at 2330 Fort Henry Drive in 1961. In 1964, Biff Burger opened at Stone Drive and Eastman Road, and a second Pal’s on Lynn Garden Drive followed. These places became the foundations of my youth—the backdrop of ballgames, cruising, first jobs, and everyday routines—very different from the Kingsport earlier generations had known.

For our grandparents, Kingsport revolved around downtown—around Church Circle, Broad Street, the train station, and walkable connections between work, worship, and commerce. For those of us who grew up after 1961, Kingsport revolved around Stone Drive, Lynn Garden Drive, Fort Henry Drive, Eastman Road, and the malls.

This generational shift came with loss. What became of the vacated spaces? In some cases, they’re still evolving five decades later. The demolition of the Kingsport Inn created what became known as the “Church Circle Parking Lot.” Construction of Lowe’s later partially blocked the historic sightline down Broad of the Clinchfield Railroad station, weakening a powerful symbolic connection to the city’s origins. These were not isolated decisions; they mirrored a national urban renewal mindset reshaping cities across America.

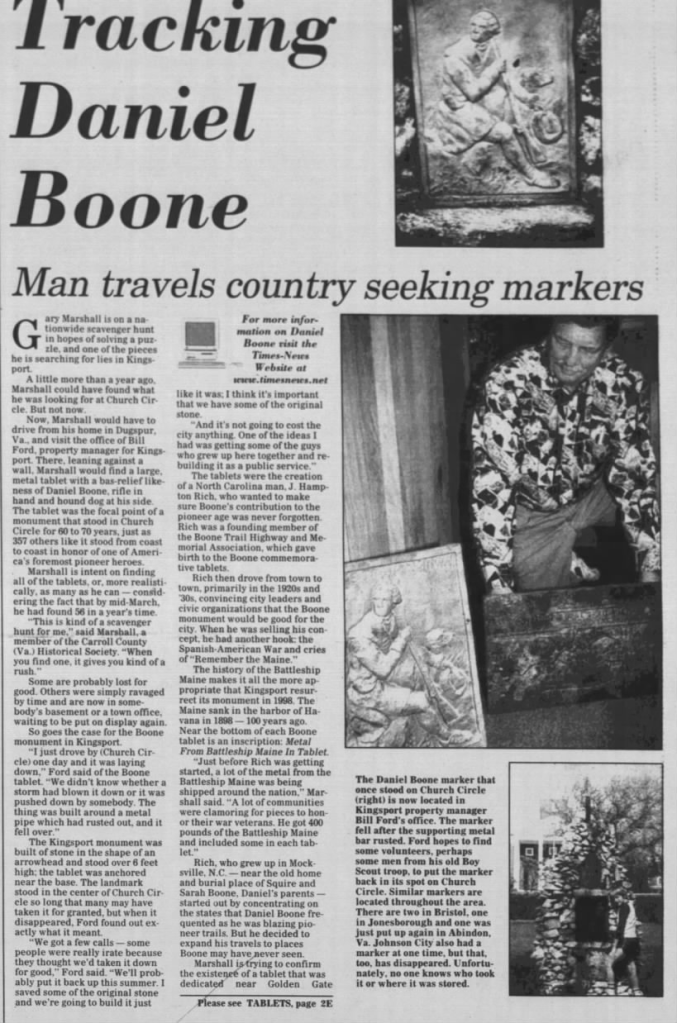

That same logic reached Church Circle directly in 1969, when a Kingsport Times-News article dated Sunday, June 1, 1969, warned that a proposed street plan “might take Church Circle.” Consultants recommended widening Sullivan Street to four lanes, a move that would have consumed the Circle itself.

Kingsport hesitated—and then chose differently.

As Stone Drive (U.S. 11W) matured as a major arterial and U.S. 23 was rerouted to a controlled-access freeway in 1982 (now known as I-26), the pressure eased. The rationale for sacrificing Church Circle evaporated but downtown became more isolated.

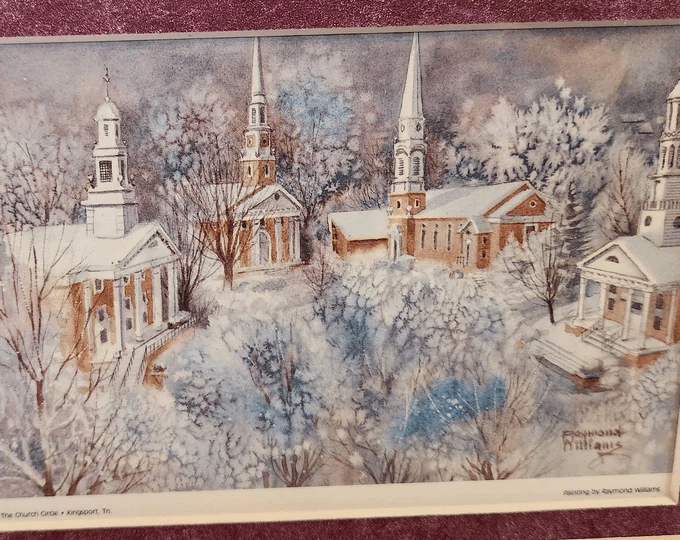

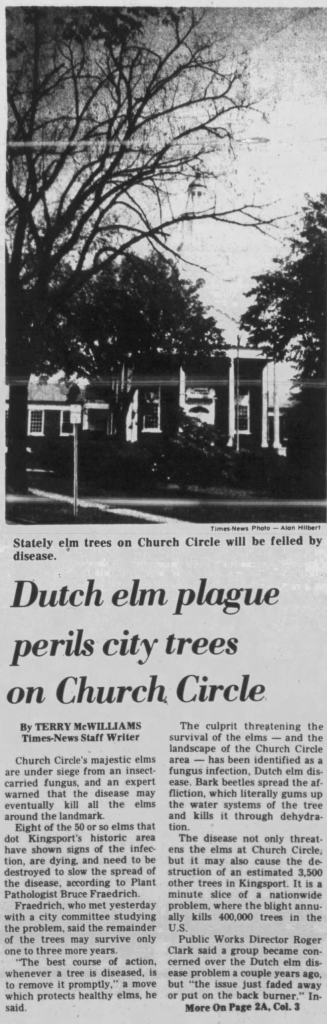

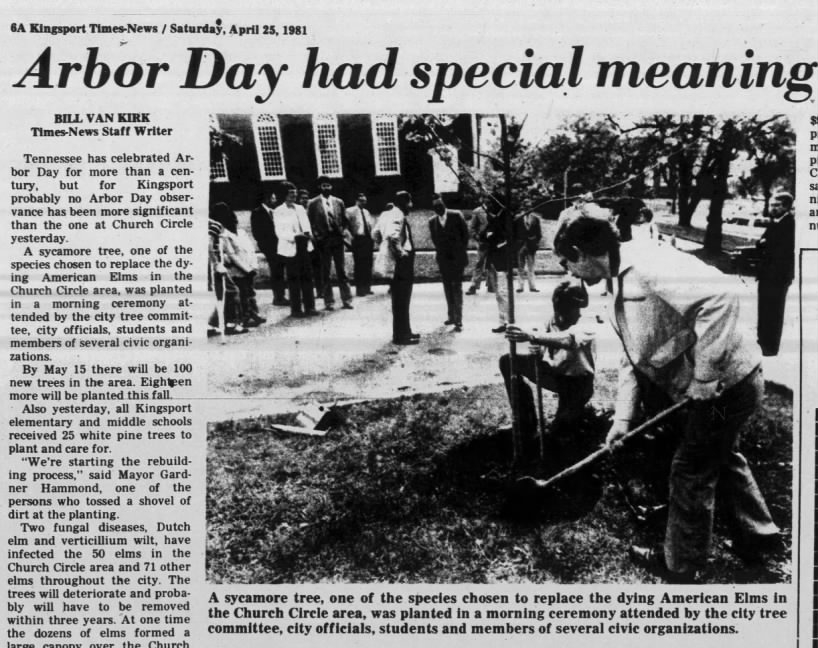

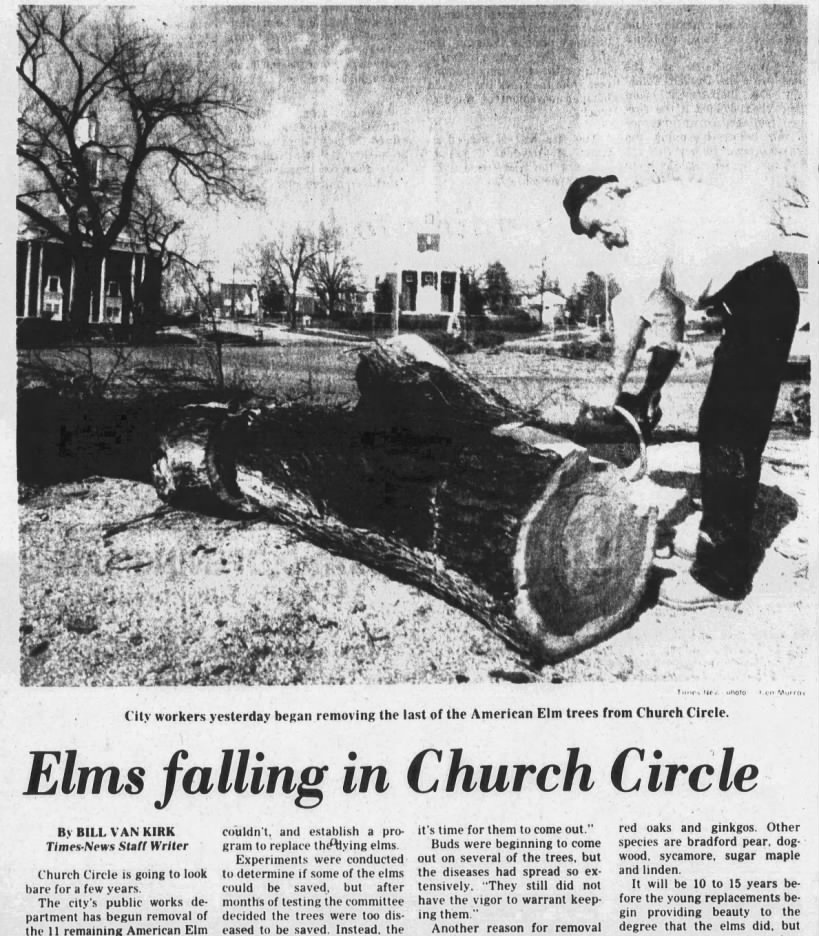

As if to add insult to injury, Dutch Elm disease claimed the remaining 16 mature elm trees planted around Church Circle by Kingsport’s original landscape architects. They were replaced by smaller maturing trees with an elm-like vase shape, but they’ll never grow as tall as their forebearers. Nothing will truly replace the stately elms.

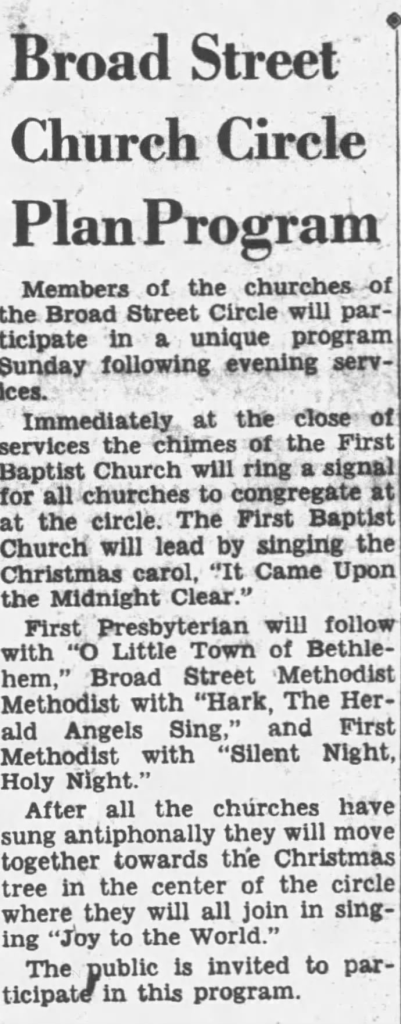

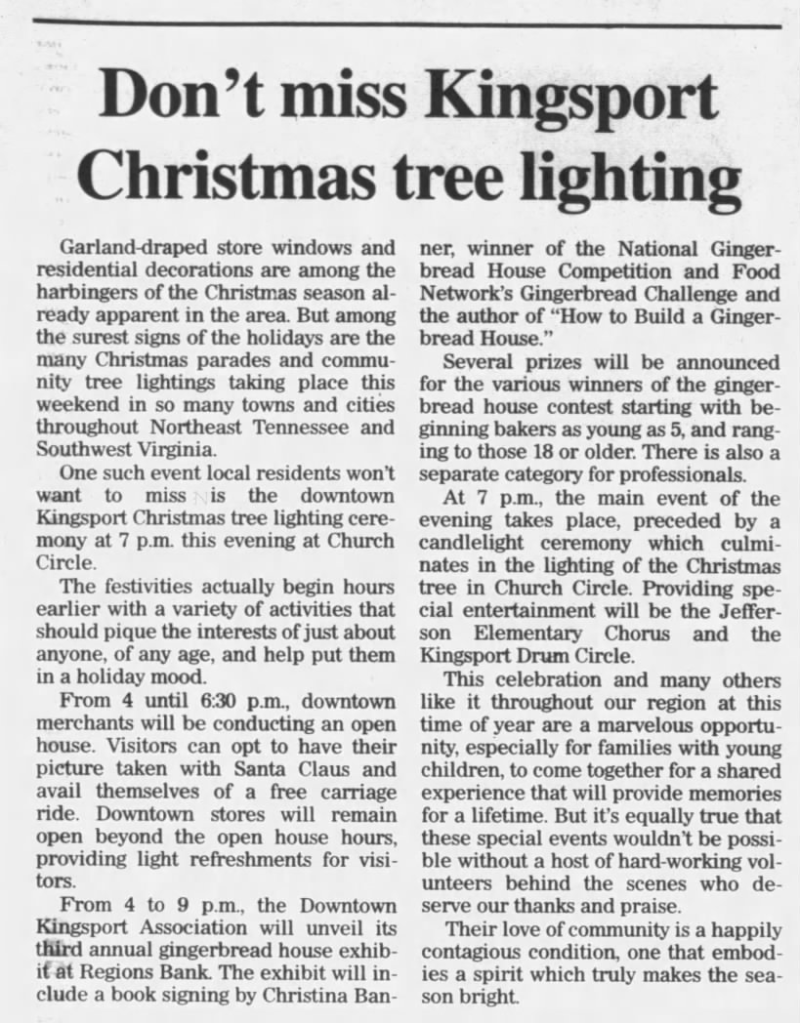

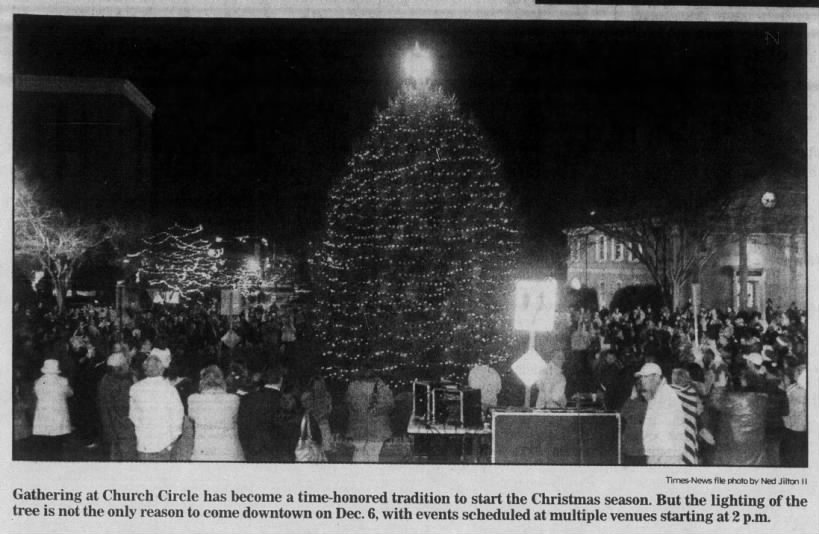

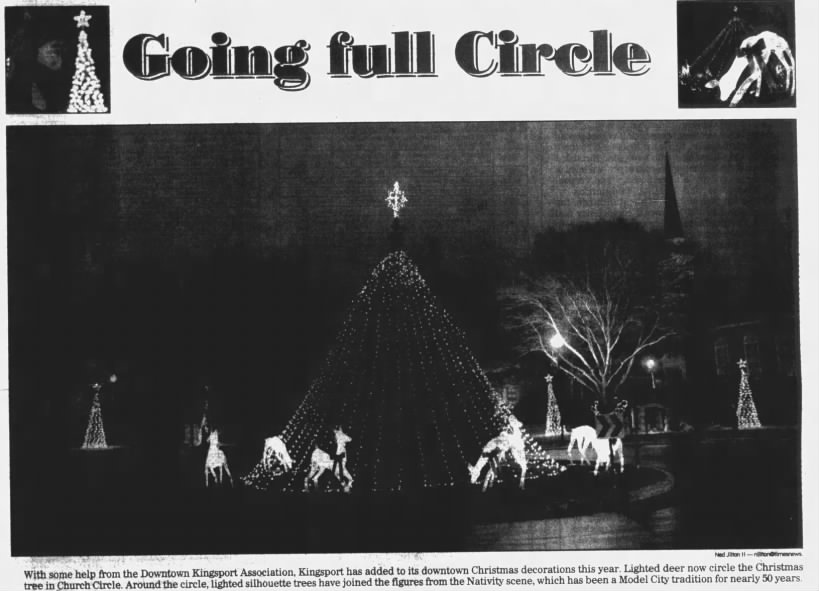

But town leaders, particularly Peggy Turner Director of the Downtown Kingsport Association, never gave up. With each setback, she saw opportunities. The circle was filled with red geraniums she affectionately called “Joe-raniums” because businessman Joe Wimberly provided the funding. She secured the herald angels to mount on the light poles around the circle at Christmas. She called them the “Harold Angels” because Harold Childress of Hamlet-Dobson paid for them.

For the next three decades, a succession of downtown advocates, city leaders, and community volunteers found ways to reimagine, redevelop, and persevere. With every door that closed, another door opened, and Kingsport seemed to embrace the change rather than fear it. Upper stories became lofts. Restaurants and breweries found spots on Main Street and off the beaten path. Event venues found eclectic homes. Light industrial warehouses became sports training facilities. Heavy manufacturing became a farmers market and professional office spaces. New residential construction found downtown in the form of apartments and single-family homes. And recently, the old JCPenney was announced as a future home for America’s fastest-growing sport—pickleball.

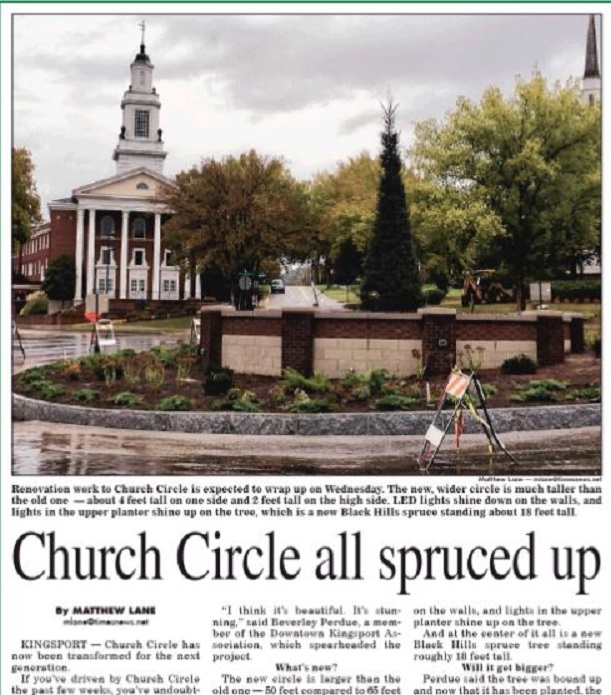

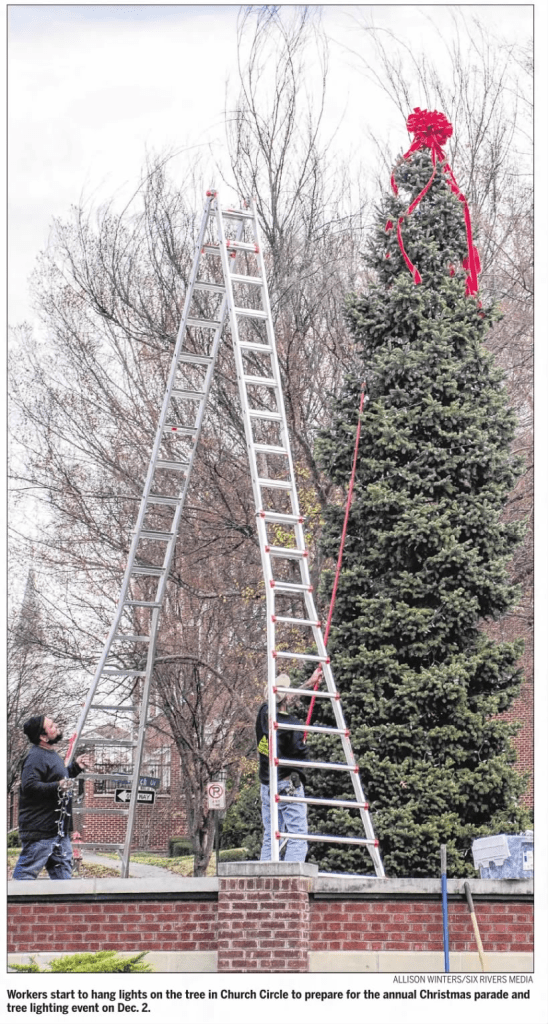

The 2017 Church Circle renovation, undertaken during Kingsport’s centennial year, marked a moment of reflection rather than reinvention. The work focused on lighting, irrigation, and vertical prominence, reinforcing the Circle’s visual and ceremonial role. That year also brought a traumatic moment. The longtime Christmas tree had to be replaced. The new tree was small—noticeably so—and some wished it had been bigger immediately. But a tree, like a city, does not grow on demand. They must first put down strong roots and anchor themselves to support growth. In a centennial year, the lesson felt appropriate. Scripture reminds us, “Let us not become weary in doing good, for at the proper time we will reap a harvest if we do not give up” (Galatians 6:9). Each year since, the tree has grown taller and fuller—perhaps imperceptibly, but true—quiet evidence that patience, stewardship, and strong foundations are what allow both trees and cities to endure.

But the grassroots work never ends. In 2024 Keep Kingsport Beautiful spearheaded a four-season plan for the circle featuring evergreens in the winter, colorful perennials in the spring, heat-resistant flowers during summer, and cool-season blossoms in the fall.

With each improvement, I just want to call Peggy Turner and see what she thinks. She would be over the moon. She seemed to know it would eventually happen if we just kept the faith. Sometimes that was easier said than done.

Kingsport’s town square—Church Circle—is so deeply a part of our identify that it appears even in the city’s logo. What many see as a sunrise rising over Bays Mountain is also a stylized representation of Church Circle itself, with radial streets extending outward. It is a visual echo of the original plan—a reminder that Kingsport was designed with intention and built with resolve.

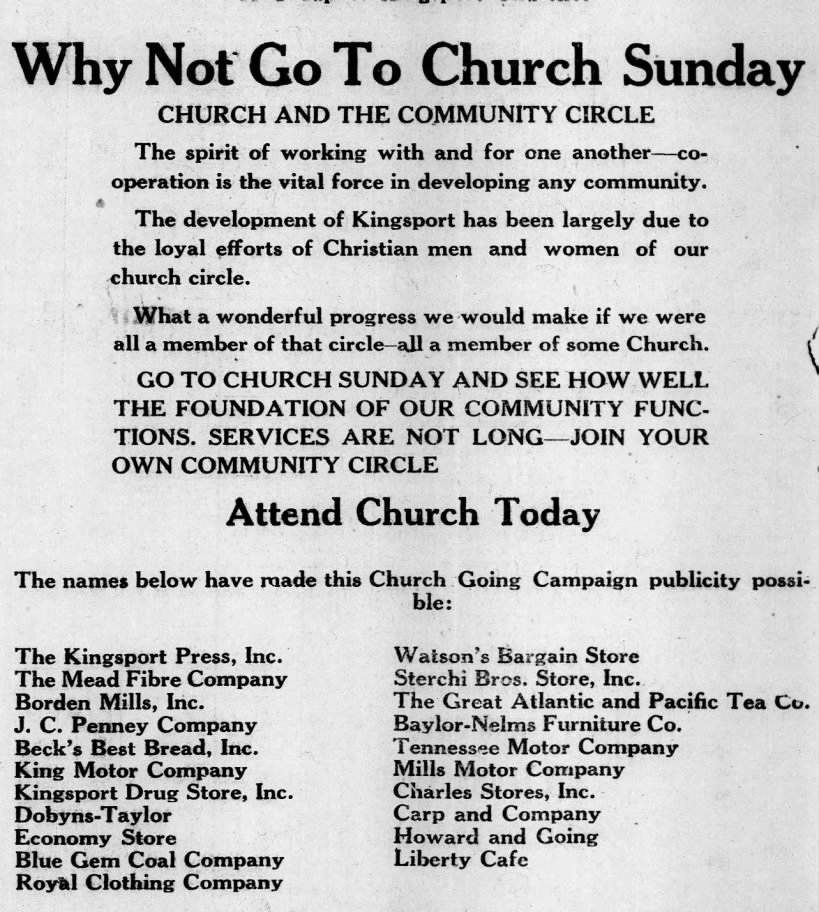

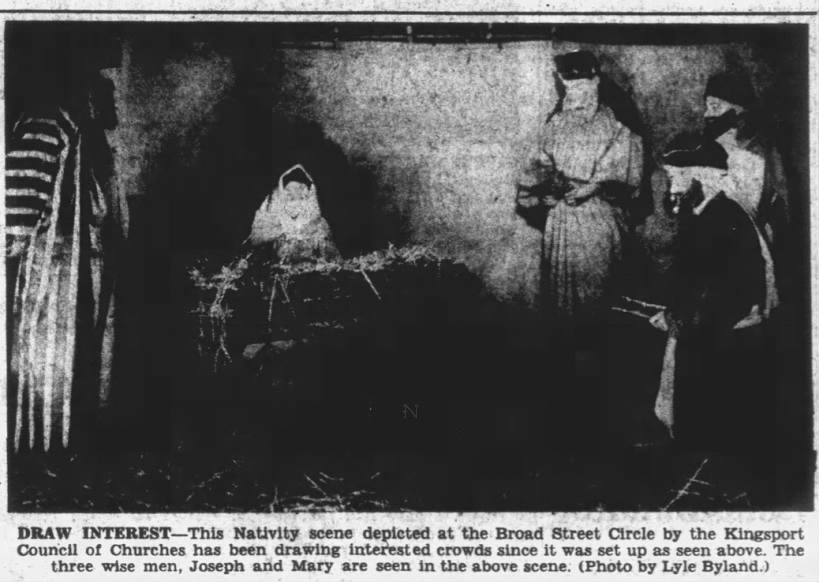

For generations, Church Circle has carried not only civic weight, but spiritual gravity. In times of world war, economic depression, and social upheaval, it was here that community leaders gathered—searching their souls, seeking wisdom, and praying for guidance before making decisions that would shape the city’s future.

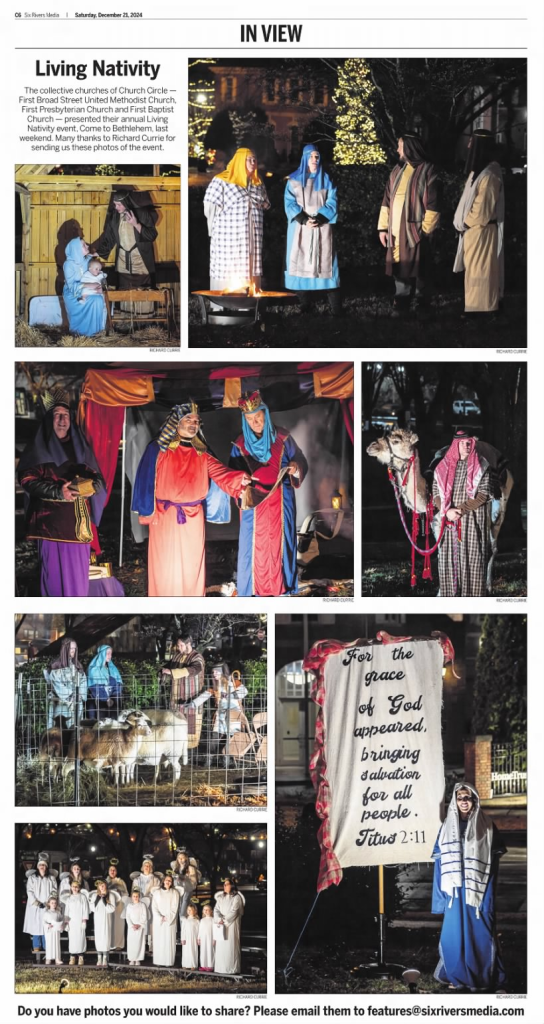

It is also where life has unfolded in its most meaningful moments. Countless births, marriages, and funerals have been marked here—joy, commitment, loss, and remembrance—reflecting the lives of those who built this town. From Church Circle, countless suburban churches were conceived and planted, carrying their missions outward as Kingsport grew. Even today, thousands of citizens turn toward this place not out of nostalgia, but out of conviction—seeking purpose, community, forgiveness, hope, and a relationship with their Creator.

Today, downtown remains the unique heart of Kingsport, not because it has the most traffic, but because it has the most meaning. It is defined not by national franchises—who will move on without loyalty or apology—but by locally owned businesses run by our friends and neighbors. They stay. They invest. They define our character.

Downtown Kingsport has the largest concentration of locally owned places to eat, shop, play, and gather anywhere in the city. That did not happen by accident. It is the result of decades of choices that preserved authenticity even when convenience tempted us otherwise.

The strength of a city is not measured by how quickly it grows or how tall it appears, but by the depth of its roots—its institutions, its locally owned businesses, its shared values, and the places that anchor civic life. Like the tree, stability comes first; growth follows.

Church Circle stands at the center of that story—literally, symbolically, and spiritually. While highways shift, malls rise and fall, and brands come and go, a city’s identity is built by what—and who—remains.

Celebrate that.

Support it.

Protect it.

Because cities that forget their centers eventually forget themselves—and Kingsport, when tested, chose to remember.

Leave a reply to hard0c80b6af7ee Cancel reply