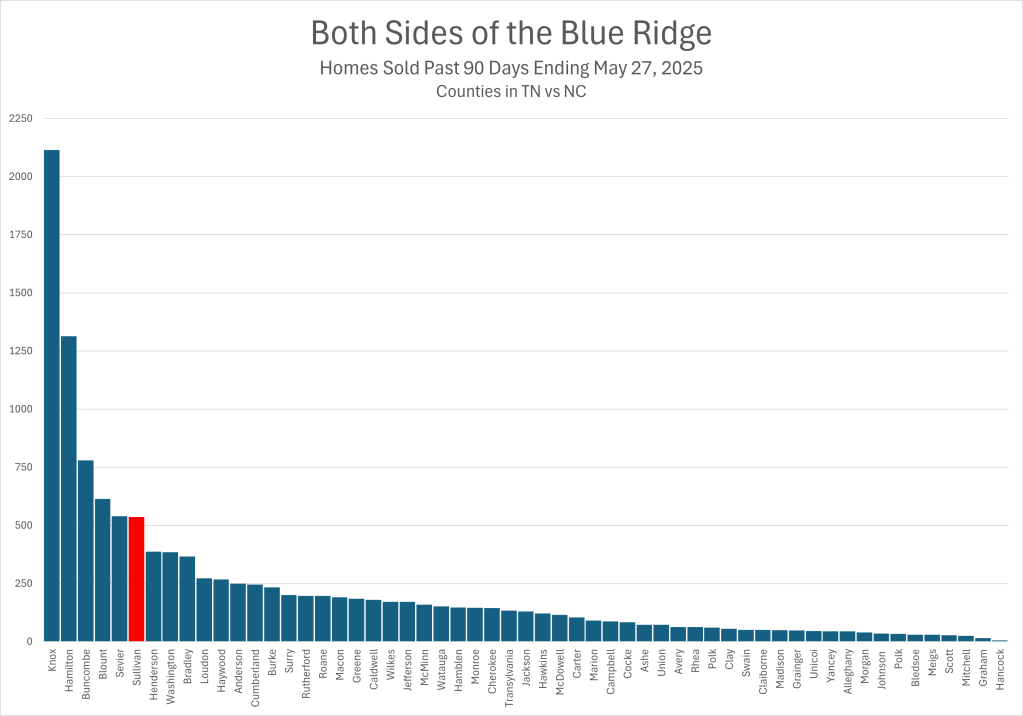

Most often we focus on cities, but let’s take a look at counties on both sides of the Blue Ridge.

Over the past ninety days ending May 26, 2025, single‐family home sales across East Tennessee and Western North Carolina have offered a revealing snapshot of regional real-estate vitality. In Tennessee’s lineup of top markets, Sullivan County—anchored by Kingsport and Bristol—is a standout performer. With 3.3 closings per 1,000 residents, Sullivan is solidly in the upper tier—behind only the largest urban and resort‐driven markets—and well ahead of most of its North Carolina counterparts.

This performance underscores both the resilience of Sullivan County’s housing market and the broader appeal of Tennessee’s economic and regulatory environment compared to its cross-border peers.

In Tennessee, the market leaders remain familiar: Knox County leads with 2,115 sales, followed by Hamilton (1,314), Blount (614), and Sevier (539). Sullivan’s 536 closings place it just behind Sevier, a county fueled by vacation-home demand around Sevierville, Pigeon Forge, and Gatlinburg, and comfortably ahead of Washington (385), Bradley (366), and Loudon (266). That means Sullivan not only holds its own against larger urban centers but also benefits from a balanced mix of affordability, employment opportunities, and quality of life.

Crossing the state line, North Carolina’s top performers—Buncombe (779), Henderson (387), Haywood (267), Burke (233), and Surry (201)—paint a different picture. Buncombe County, home to Asheville’s booming tourism and arts scene, posted 779 sales, ahead of Tennessee’s Sevier and Sullivan counties. Yet the gap narrows quickly: after Buncombe, Henderson County’s 387 and Haywood’s 267 fall below Sullivan’s tally. This suggests that while some North Carolina markets enjoy premium pricing and demand, the average North Carolina county lags behind Tennessee’s mid-tier markets in transaction volume.

Several factors help explain Sullivan County’s relative strength. First, Tennessee’s lack of a state income tax gives residents greater purchasing power and keeps more dollars circulating locally. Lower closing costs and streamlined regulatory requirements further reduce barriers to homeownership. Meanwhile, the Tri-Cities region continues to diversify its economic base—health care, advanced manufacturing, and logistics all contribute to stable job growth.

In contrast, North Carolina’s property taxes are generally lower than those in many states, but local tax rates and fees can vary widely by county. Development rules near sensitive mountain watersheds are often stricter, constraining new supply and driving prices higher—particularly around Asheville. Outside of the urban core, many North Carolina counties struggle with aging housing stock, population decline, or limited employment growth, all of which can temper buyer activity.

For prospective homeowners weighing Tennessee against North Carolina, Sullivan County offers a compelling middle ground: more affordable home prices than many North Carolina resort markets, yet stronger sales velocity than rural Tennessee counties. Buyers benefit from Tennessee’s pro-business climate while enjoying the region’s rolling hills, access to the Cherokee National Forest, and the cultural amenities of the Tri-Cities. From a public-policy perspective, Sullivan’s performance illustrates how lower taxes, infrastructure investment, and economic diversification can combine to sustain a healthy housing market.

In summary, Sullivan County’s 536 single-family home sales over the last ninety days place it firmly among East Tennessee’s commercial engines. It outperforms most neighboring North Carolina counties and holds its own against larger Tennessee markets. For families, retirees, and investors alike, the dynamics of Tennessee versus North Carolina continue to shape where people choose to live—and in that competition, Sullivan County is proving that the home turf of Kingsport and Bristol remains as competitive and welcoming as ever.

Leave a comment