We hear a lot about housing affordability these days. The real challenge is distinguishing between national trends that affect everyone and local conditions that vary by community.

Our perception of the data is shaped not just by statistics but also by our age and lived experiences.

I once knew a Realtor who entered the market around 2012—just four years after the Great Recession of 2008. In a presentation, he humorously expressed his optimism, saying, “This is the best year I’ve ever seen in all my years in real estate,” which drew knowing laughter from veteran agents who remembered pre-recession markets. Ah, the good ol’ days.

Think about a major historical moment in your lifetime—D-Day, Kennedy’s assassination, or the 9/11 attacks. To remember D-Day, you’d need to be at least 85 today; to recall JFK, at least 68; and for 9/11, at least 28. It’s all a matter of perspective. The housing market is no different. It’s all about context.

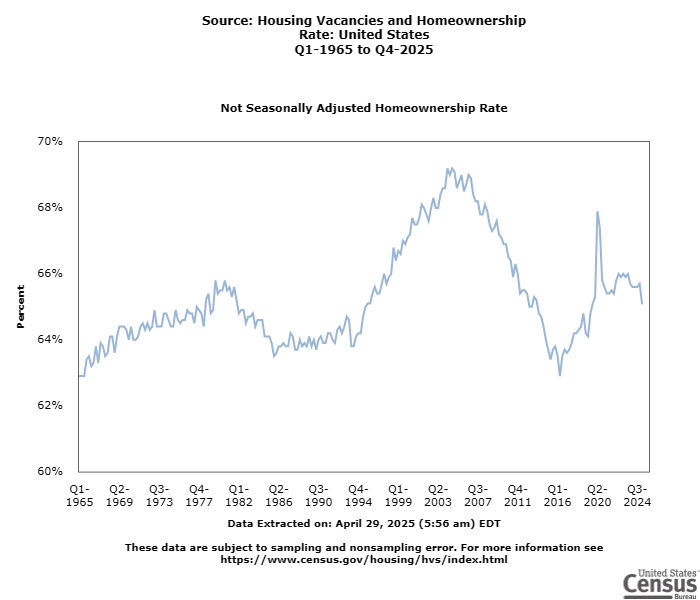

Homeownership is one of the clearest reflections of housing affordability. Surprisingly, the homeownership rate today is actually 2.2% higher than it was 60 years ago. In Q1 1965, the Census Bureau reported that 62.9% of U.S. homes were owner-occupied. As of Q1 2025, it stands at 65.1%. But in those 60 years, the rate has shifted significantly, rising and falling with the economy, inflation, demographic trends, and public policy—some of which turned out to be short-sighted or irresponsible.

Homeownership is a meaningful and rewarding goal—it offers stability, the chance to build equity, and a sense of personal accomplishment. But it also means more than just lower interest rates, smaller downpayments, or more favorable mortgage terms. It comes with serious responsibilities. Unlike renting, owning a home means being prepared for ongoing costs like maintenance, property taxes, insurance, and unexpected repairs. It requires a reality check of wants vs. needs, careful budgeting, and a long-term financial mindset, which are challenging in today’s consumer economy where we’ve learned to swipe a card and worry how to pay later. That’s a formula for disaster as we learned in the 2008 recession.

From 1965 to 1980, homeownership steadily increased, driven by strong economic growth, the expansion of suburbs, and easy access to affordable, federally backed mortgages like those through the FHA and VA. Middle-class wages grew faster than housing costs, making it feasible for many families—often on a single income—to purchase homes. The interstate highway system enabled suburban growth, and the cultural ideal of homeownership was deeply ingrained. By Q1 1981, the homeownership rate had reached 65.6%.

Between 1981 and 1994, however, that rate declined as economic conditions worsened. The early ’80s brought mortgage interest rates as high as 18% in an effort to tame inflation. Monthly payments skyrocketed, even as home prices remained flat. Recession, job losses, wage stagnation, and a changing job market all made homeownership harder to achieve, especially for younger Baby Boomers. Social trends like delayed marriage and longer periods of renting also played a role. By Q1 1994, the rate had dropped to 63.8%.

Then came a sharp increase from 1994 to 2006. Economic expansion, federal homeownership initiatives, and looser mortgage lending—including subprime loans—made homeownership more accessible. More people qualified for mortgages through low down payments and relaxed lending standards. However, this surge in access brought risk. Many of the loans were unstable, and when housing prices began to fall, the wave of defaults sparked the 2008 financial crisis. Homeownership declined sharply, bottoming out at 63.5% in Q1 2016.

From 2016 to 2020, U.S. homeownership increased due to a combination of strong economic growth, rising wages, low unemployment, and historically low mortgage interest rates. After years of recovery from the 2008 housing crash, consumer confidence improved, and more Americans—especially Millennials reaching their late 20s and 30s—entered the housing market for the first time. Mortgage rates fell to near-record lows during this period, making monthly payments more affordable even as home prices rose. Looser credit conditions compared to the immediate post-crisis years also made it easier for more people to qualify for loans. In addition, a growing shortage of rental housing and steadily increasing rents encouraged many renters to transition into homeownership. Together, these factors reversed the post-recession decline and pushed homeownership rates higher by the end of the decade.

But since 2020, homeownership has declined again—this time due to sharply rising mortgage rates, limited housing supply, and continued increases in home prices. Inflation and economic uncertainty have made it harder to buy and keep a home, especially for younger buyers. Although homeownership remains more common today than it was in the mid-1960s, when rates hovered around 63%, it has fallen from the historic highs seen in the early 2000s and is now trending closer to long-term averages.

The future of homeownership faces major challenges, including rising home prices, higher mortgage rates, and a persistent shortage of affordable homes. Consumer debt, student debt, growing wealth inequality, and climate risks are making it harder for many Americans—especially younger and lower-income households—to buy and maintain homes.

A reminder. Everything you just read above is based on national conditions beyond local control.

But local governments can play a role by expanding housing supply and partnering with developers and Kingsport has done just that. Infrastructure–roads, water, sewer–has been methodically expanded to support development. Updated zoning laws allow a wider mixture of housing types with increased density—townhomes, duplexes, and smaller single-family homes—to make it easier to build more affordable options. At the same time, offering incentives where appropriate, such as fast-track permitting, responsive building inspections, and tax abatements encourages private developers to invest in workforce and entry-level housing.

However, overcoming local opposition, often driven by NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) attitudes, will be critical. We need a range of housing options to meet all price points. If we want the next generation to be able to buy a home, we have to let builders build.

At the end of the day, homeownership in the Kingsport area remains strong: 75.2% in Sullivan County and 79.5% in Hawkins County—well above the national average. That’s a testament to sound local planning and community values. But there’s always room to do more—and do better.

Leave a comment