I was recently talking with colleagues about the early development of modern Tennessee and why the first counties were incorporated in two pockets: East Tennessee along the upper Tennessee Valley and Middle Tennessee along the Cumberland River basin, initially leapfrogging Southeast Tennessee and the Cumberland Plateau. I couldn’t find a succinct description, so I decided to create one. History doesn’t always evolve chronologically, it overlaps. Here’s an attempt to make it make sense.

NATIVE AMERICANS (PRE-1540)

Before today’s Cherokee, Chickasaw, Creek (Muscogee), Shawnee, and Yuchi, Tennessee was shaped by earlier Woodland and Mississippian peoples. During the Woodland period (c. 1000 BCE–1000 CE), communities built burial/ritual earthworks, adopted pottery and the bow-and-arrow, and joined long-distance trade networks; classic sites include Pinson Mounds (near Jackson), Old Stone Fort (near Manchester), and mound-and-ditch complexes along the Cumberland and Tennessee River valleys. In the Mississippian era (c. 1000–1600 CE), larger town-centered societies with maize fields, plazas, and platform mounds flourished at Mound Bottom (near Kingston Springs, west of Nashville), Shiloh Mounds (near Savannah), Hiwassee Island (near Dayton), and Castalian Springs/Sellars Farm (near Gallatin/Lebanon). After 1500, disease, conflict, and migration fractured these chiefdoms and new identities formed. By the 1700s, the Cherokee Overhill towns—Chota, Tanasi, Toqua, Citico, Great Tellico, Tuskegee—clustered along the Little Tennessee River (around today’s Vonore/Tellico Lake); the Chickasaw held sway in the west around the Chickasaw Bluffs (Memphis) and the Hatchie/Forked Deer country (Jackson, Ripley); Shawnee and Creek (Muscogee) parties hunted and contested Middle Tennessee in the Cumberland and Duck River basins (Nashville, Clarksville, Columbia); and Yuchi communities persisted along the Hiwassee and lower Tennessee rivers (near Cleveland and Chattanooga)—often residing atop earlier Woodland and Mississippian landscapes.

EUROPEAN CONTACT (1540-1756)

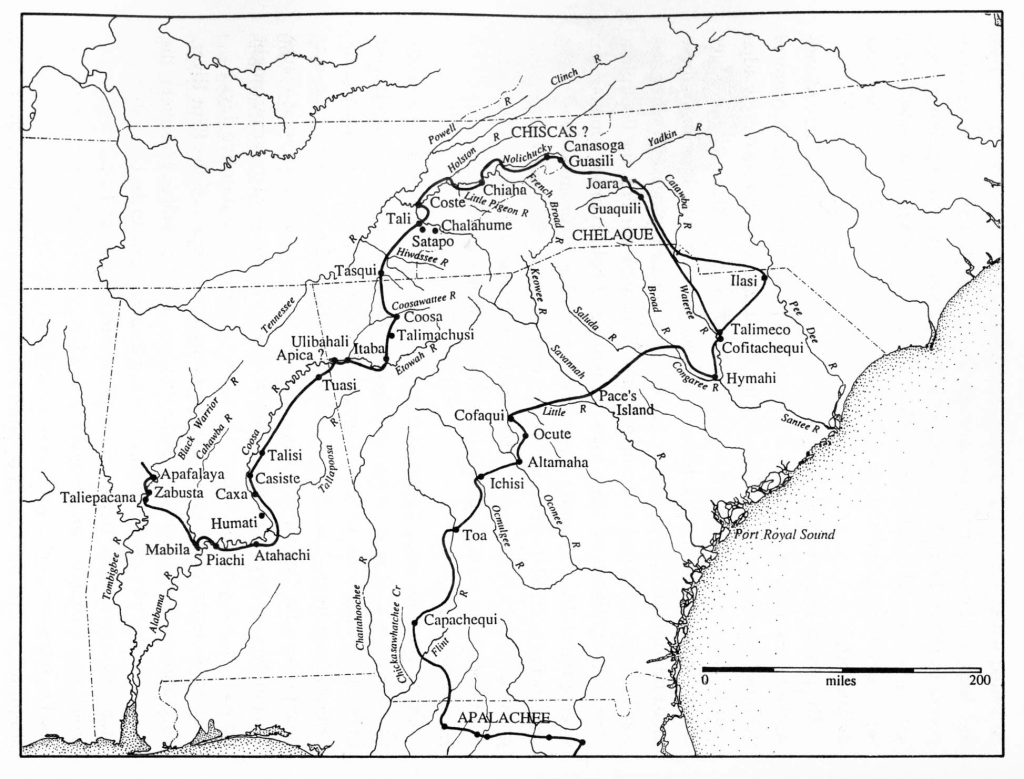

The first documented European contact is the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto in 1540 when he crossed into today’s Northeast Tennessee (near modern Erwin) following the Nolichucky River, staying weeks at Chiaha/Olamico on Zimmerman’s Island (now under Douglas Lake) near modern Dandridge, then moving to Coste at Bussell Island (mouth of the Little Tennessee), up to Tali/Toqua site (modern Vonore, TN), crossing the Hiwassee, and exiting by the Ocoee–Conasauga portage toward Coosa (modern Chatsworth, GA). In 1566–68 Juan Pardo‘s expedition from Santa Elena (modern Beaufort, SC) led to the building of interior forts to secure Spain’s route, including Fort San Juan at Joara (Morganton, NC) and Fort San Pedro beside Chiaha (Dandridge). Natives destroyed the garrisons within a year, ending Spain’s inland foothold. The Pardo party’s documented travels include a trip up the middle fork of the Holston River to Chisca (Saltville, VA). After epidemics and upheaval, native peoples coalesced into new communities; by the late 1600s the Cherokee Overhill towns were rising in the Little Tennessee valley. English traders pushed in from Virginia and Carolina—most notably James Needham and Gabriel Arthur (1673–74), who reached the Overhill towns to open direct trade. Meanwhile, on the Mississippi, the French appeared: in 1682 La Salle passed the Chickasaw Bluffs (modern Memphis) and briefly stockaded Fort Prudhomme in West Tennessee while claiming the valley for France; by the 1680s–90s, Shawnee villages and a French post stood at French Lick (present-day Nashville).

(Charles Hudson, University of Georgia)

COLONIAL ERA (1756-1763)

The lands that would become Tennessee fell along rivers flowing west toward the Ohio–Mississippi Rivers, long treated as French Louisiana—and hints are found in the geographic names–the French Broad River (the “other” Broad Rivers ran through South Carolina to the Atlantic seaboard, which was English) and French Lick (Nashville). Before France relinquished its claims, three British forts were erected: in 1756 Colonial Virginia troops built a small “Virginia Fort” opposite Chota, the political center of the Overhill Cherokees on the Little Tennessee River; in 1757 Colonial South Carolina raised Fort Loudon five miles downstream; and, after relations collapsed and Loudon fell under siege, Colonial Virginia erected Fort Robinson in 1761 at the Long Island of the Holston (Kingsport) as a forward base to compel peace. Fort Robinson was later renamed “Fort Patrick Henry” during the American Revolution.

FRENCH TO BRITISH TRANSFER (1763)

The geopolitical map shifted on February 10, 1763, when the Treaty of Paris ended the Seven Years’ War and France ceded its mainland claims east of the Mississippi to Britain. That autumn, London drew the Royal Proclamation Line along the Appalachian crest to pause new settlement while officials negotiated boundaries with the Cherokee. The problem is, the Appalachian crest isn’t as identifiable as it sounds, so settlers interpreted it generously, settling much farther west than the crown intended.

TREATY OF LOCHABER & DONELSON’S LINE (1770-1772)

To sort the confusion after 1763, the Treaty of Lochaber (October 18, 1770) reset the Cherokee–Virginia/Carolina boundary from a point six miles east of Long Island of the Holston (Kingsport) northward to the Kanawha River (today’s Charleston, WV). That’s why early settlement near Kingsport was located along Reedy Creek and Fall Creek six miles east of Long Island. In 1771, John Donelson surveyed the new line— “Donelson’s Indian Line”—tracing the Holston so that more trans-Appalachian ground fell under Virginia’s umbrella yet left Watauga, Nolichucky, and Carter’s Valley south of the line on Cherokee land. Those settlements therefore relied on Cherokee leases (1772) and later purchases (1775) to regularize their presence. Civilian farming neighborhoods followed just beyond the 1763 Proclamation Line at the decade’s end: Evan Shelby’s North of Holston/Sapling Grove (Bristol area); William Bean’s 1769 cabin on Boone’s Creek near today’s Johnson City; the clustered Watauga Settlements around Sycamore Shoals (Elizabethton), which organized the Watauga Association in 1772; parallel communities in Carter’s Valley (Hawkins County); and Jacob Brown’s Nolichucky settlement (1771–1772), established by lease/purchase from the Cherokee.

DANIEL BOONE (1775)

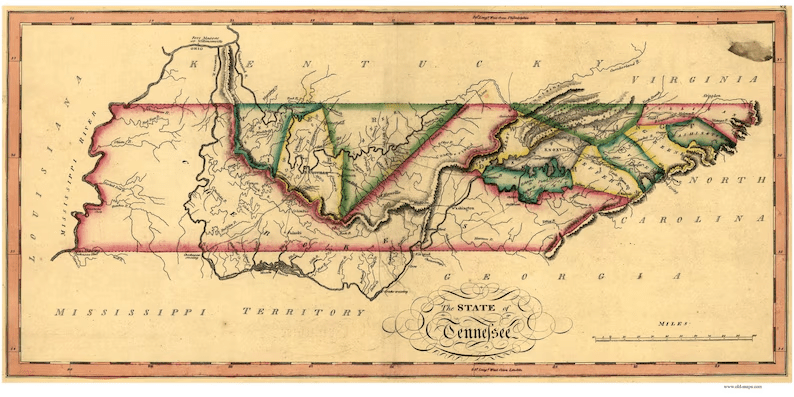

On March 10, 1775, Daniel Boone and roughly three dozen axmen set out from Long Island of the Holston (Kingsport) and cut the Wilderness Road through Powell Valley and Cumberland Gap to the Kentucky River, turning Long Island from a defensive foothold into a migration gateway that tied the Holston–Watauga world to Kentucky and the headwaters of the Cumberland River, which dipped south back into Tennessee towards modern Nashville (see map).

(date of Tennessee statehood)

DONELSON & ROBERTSON PARTIES (1779-1780)

In the winter of 1779–80, two parties left the Long Island of the Holston (Kingsport) corridor to plant Middle Tennessee. James Robertson led the overland advance: after scouting French Lick in spring 1779, he returned with settlers in late 1779 and was on the Cumberland by Christmas Day, 1779 (many accounts mark Jan 1, 1780 as the founding moment). Meanwhile, John Donelson launched the boat Adventure and a flotilla from Fort Patrick Henry on the Holston at Kingsport on December 22, 1779, ice-delayed at Reedy Creek, and—after a four-month, 1,000-mile river run—landed at French Lick on April 24, 1780. With both parties united, the settlers adopted the Cumberland Compact in May 1780, formalizing government at the Bluff (Fort Nashborough), the nucleus of Nashville.

REVOLUTIONARY WAR (1775–1783)

As the American Revolution began in 1775, the backcountry became its own battlefield. On July 20, 1776, Cherokee war leader Dragging Canoe launched a three-pronged offensive; local militia marched out from Eaton’s Station and won the Battle of Island Flats (Kingsport) in the ravines off today’s Memorial Boulevard at Warpath Drive, keeping the Long Island crossing—and Boone’s new thoroughfare—open. Civil government took root even as the war raged: Washington County, North Carolina formed in 1777 with Jonesborough as seat; Sullivan County followed in 1779, organizing its first court at Moses Looney’s Fort, 567 Island Road, Kingsport. The tide turned with Yorktown (1781), and by 1783 the peace treaty was signed as Greene County (Greeneville) and Davidson County (Nashville) were created.

“SQUABBLE STATE” BOUNDARY DISPUTE BEGINS (1779)

Meanwhile, the boundary between Virginia (and by extension, Kentucky) and Tennessee (then North Carolina) became its own drama. By charter the Virginia–Carolina line should have run at 36°30′, but Dr. Thomas Walker (for Virginia) and Richard Henderson (for North Carolina) produced two rival 1779 surveys—Walker’s more southerly, Henderson’s to the north—leaving a narrow overlap of disputed jurisdiction across the Holston country, later nicknamed the “Squabble State.” Caught between the Walker and Henderson surveys, the Holston settlements lived for years in a kind of dual-jurisdiction limbo—paying taxes, filing deeds, and mustering militia under whichever legislature would recognize them that season. Not surprisingly, a few local heavyweights served both governments. John Tipton held office in Virginia before representing Washington County in North Carolina’s Senate and later serving in territorial and Tennessee posts; William Cocke likewise crossed lines, holding seats in Virginia and North Carolina before becoming one of Tennessee’s first U.S. senators. Only when North Carolina adopted Walker’s line in 1790, Virginia concurred in 1791, and both states agreed to the 1802–03 compromise line—later treated as final by the Court—did the map and everyday life finally match. The true 36-30 parallel became the Tennessee-Kentucky line west of the Tennessee River in West Tennessee. But for an early mistake, Kingsport and Bristol would be entirely in Virginia, Johnson City in Tennessee, and Clarksville in Kentucky. How different our lives might have been!

OVERMOUNTAIN MEN & KING’S MOUNTAIN (1780)

The same communities that defended Island Flats in 1776 mounted one of the war’s decisive marches: over 600 Overmountain riflemen mustered at Sycamore Shoals (Elizabethton) on September 25, 1780, crossed the high gaps, and on October 7, 1780 overran Major Patrick Ferguson at King’s Mountain—a short, sharp Patriot victory considered the turning point of the war. The British southern plan was thwarted, morale was lifted, and Cornwallis surrendered in 1781. Many King’s Mountain veterans received land grants to populate North Carolina’s lands that would ultimately become Tennessee.

POST-REVOLUTIONARY WAR & STATE OF FRANKLIN (1784–1789)

In the postwar vacuum, the “State of Franklin” (1784–1788) under John Sevier declared independence from North Carolina. County-building continued: Sumner County (seat Gallatin) and Hawkins County (seat Rogersville) formed in 1786, and Tennessee County (seat Clarksville) in 1788—an entity that would be extinct in 1796 when its lands were divided at statehood. Sevier was arrested for treason by North Carolina in 1788, pardoned, then elected to the North Carolina Senate (1789) from Greene County, where he supported ceding the western lands to the United States.

SOUTHWEST TERRITORY (1790–1796)

North Carolina surrendered the West in 1790, creating the Territory South of the River Ohio (the Southwest Territory). George Washington appointed William Blount territorial governor and superintendent of Indian affairs; he opened the seat at Rocky Mount (Sullivan County) and, in 1792, shifted it to James White’s Fort—the origins of Knoxville. John Sevier was named brigadier general of the Washington District militia (1790) and resumed frontier defense and diplomacy on the Holston/Watauga. In his August 13, 1790 letter to Henry Knox, Washington pressed for Indian trade regulations, steps to restrain hostilities, a proclamation against illegal encroachments, instructions for the territorial governor (including his residence), consideration of a post at the mouth of the Tennessee, and reform of western supply contracts.

Institutions multiplied: Knox County formed in 1792 (seat Knoxville), and Jefferson County in 1792 (seat Dandridge, honoring Martha Dandridge Washington). Sevier County followed in 1794 (seat Sevierville). Blount College was founded in 1794 (the seed of the University of Tennessee). Blount County formed in 1795 (seat Maryville, named for the governor’s wife). Blountville was laid out in 1795 as Sullivan County’s seat. Sevier served in the territorial House (1794–1796), rising to Speaker.

TENNESSEE STATEHOOD & EARLY LEADERSHIP (1796–1800)

On June 1, 1796, Congress admitted the State of Tennessee. John Sevier became the first governor; William Blount and William Cocke were the first U.S. senators; and Andrew Jackson won the single at-large House seat. The “Blount Conspiracy” (1797) to assist Britain in seizing Spanish Florida and French Louisiana soon surfaced; at President John Adams’ request the Senate expelled Blount (1798). Back home he was elected to the Tennessee senate (1798) and served until his death in 1800.

TENNESSEE’S SPORADIC SETTLEMENT PATTERN (1770s–1819)

Throughout, settlement followed geography and law. Northeast Tennessee filled first along the Watauga, Nolichucky, and Holston—parallel valleys with decent bottomland and familiar approaches from Virginia via Great Wagon Road spurs and the Great Indian Warrior’s Path—producing courthouse towns like Jonesborough, Greeneville, Rogersville, and Blountville. Middle Tennessee advanced almost simultaneously because settlers made a bold leap to French Lick (Nashville) in 1779–80: the Cumberland River was a true shipping highway; James Robertson went overland while John Donelson came by boat; and North Carolina land grants pulled veterans and speculators west, so stations and counties radiated along navigable water from the start. By contrast, the Knoxville–Chattanooga corridor lagged because it was the Cherokee heartland on the Tennessee, Little Tennessee, and Hiwassee Rivers, legally closed to outsiders until later treaties. Steep ridge approaches, twisty river reaches, and the Muscle Shoals choke downstream made the Tennessee a poor early freight route compared to the Cumberland. Only after federal authority settled in the 1790s and cessions followed did Knoxville (after 1792) and Ross’s Landing/Chattanooga (after 1819) grow rapidly.

CONCLUSION

In the 18th century, a distant king used simple language to define the boundaries of what is now Tennessee–language that was too simple for the geographic complexities encountered. Colonial Virginians spilled into the Holston Valley while Carolinians settled the Watauga and Nolichucky. From there, a wave moved through Kentucky to the Cumberland headwaters, settling around today’s Nashville. The settlement of West Tennessee followed in the 19th century, and Southeast Tennessee after the Trail of Tears. The three stars on the Tennessee flag represent the three grand divisions–east, middle, west–surrounded by a circle of unity.

And Tennessee’s story finally makes more sense.

Leave a comment