This weekend, Exchange Place will be abuzz for the Fall Folk Arts Festival. If you’ve never been, you should consider it.

As you drive along Orebank Road through some of Kingsport’s most desirable neighborhoods, a cluster of cabins and buildings suddenly appears like a movie set on the eastern end of the Kingsport Greenbelt.

There are clues in the surrounding place names: John Gaines Boulevard, Preston Woods, Preston Park, Eden’s Ridge, Stuart’s Run and Pendleton Place. But how do they connect? What is Exchange Place? Why is it important?

Exchange Place Living History Farm interprets a working Northeast Tennessee farm of the 1830s–1850s. In 1750 (26 years before our nation’s independence), the tract entered a 3,000-acre Virginia grant from British Colonial Governor Robert Dinwiddie to Edmund Pendleton.

Officials then believed the area lay in Virginia along the intended 36°30′ line; when commissioners finally ran the Virginia–North Carolina boundary west (1779–1780), the Reedy Creek/Eden’s Ridge country proved south of the line—legally North Carolina (later Tennessee). Virginia-issued claims like Pendleton’s were “perfected” under North Carolina law and later honored by Tennessee after the region cycled through Washington and Sullivan Counties (N.C.), the State of Franklin, the Southwest Territory, and statehood in 1796.

Pendleton never settled the tract. He tasked his nephews, James and Thomas Gaines, to sell it in ~200-acre parcels shaped by creeks and ridges across the Reedy Creek watershed feeding the Holston River and the corridor later called the Great Stage Road, with parcels reaching toward the bottomlands near Long Island of the Holston.

Thomas’s grandson, John Strother Gaines—a War of 1812 veteran—married Letitia Dalton Moore (his double second cousin), established a homestead on Reedy Creek, raised twelve children, and amassed more than 2,000 acres. An entrepreneur and postmaster, he operated a store and stage stop on the Great Stage Road (which he rerouted to his door). The name “Exchange Place” reflects the steady swapping of horses, the bartering of goods, and especially the exchange of Virginia and Tennessee currencies in the pre-national-banking era. The broader kin network included Gen. Edmund Pendleton Gaines—Andrew Jackson’s fellow War of 1812 commander and the namesake of Gainesville, Florida; Gainesville, Georgia; and other places—himself named for the statesman Edmund Pendleton.

In 1845 Gaines traded 1,182 acres—including the Main House and outbuildings—to Abingdon merchant (and first mayor) John Montgomery Preston for Holston Springs, a noted mineral-springs resort on the North Fork of the Holston in Scott County, Virginia (near today’s Gate City/Weber City). Known earlier as “McHenry’s Springs,” the site featured a large hotel operating by the early 1800s and drew health-seekers for its mineral waters. Period accounts tie the property to regional travel networks and, during the Civil War, local memory holds that the “Holston Springs Mansion” served as a Confederate hospital. Preston had invested in and improved Holston Springs as part of a broader portfolio; by exchanging it for Exchange Place, Gaines shifted from his vast Reedy Creek farm to a destination property with commercial and hospitality potential.

Preston managed Exchange Place as an absentee owner and later deeded it to his son James after James’s 1847 marriage to Catherine Greenway. James and Catherine lived there from 1850 until after the Civil War, raising six children to adulthood. James used enslaved and tenant labor—freeing two men, Jefferson and King, in 1856—produced corn, wheat, oats, and tobacco, and raised hogs. He closed the public stage stop and post office and operated the store only for tenants.

The Prestons belonged to the influential Smithfield/Greenfield clan whose marriages tied Southwest Virginia to Kentucky’s political dynasties; through these connections the family intersected with lines that produced governors such as Charles A. Wickliffe and his grandson John C. W. Beckham. Their legacy also threads through higher education: in 1872, when Virginia organized its federal “land-grant” college, the state acquired the Preston & Olin Institute and adjoining Preston family acreage at Solitude in Blacksburg—forming the nucleus of what became Virginia Tech. And in Louisville, the Preston imprint endures in Preston Street/Preston Highway, reflecting the family’s early landholding and surveying influence.

The Preston family owned Exchange Place—calling it their “Tennessee Farm”—for 125 years. In 1970 they donated seven acres of the original homestead, including the Main House and dependency buildings, to the Netherland Inn Association. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the site has grown to about sixty acres with restored and reconstructed buildings, heirloom gardens, and heritage livestock and poultry. During festivals and special events, artisans and costumed interpreters demonstrate open-hearth cooking, blacksmithing, spinning, weaving, and other “old-time” skills.

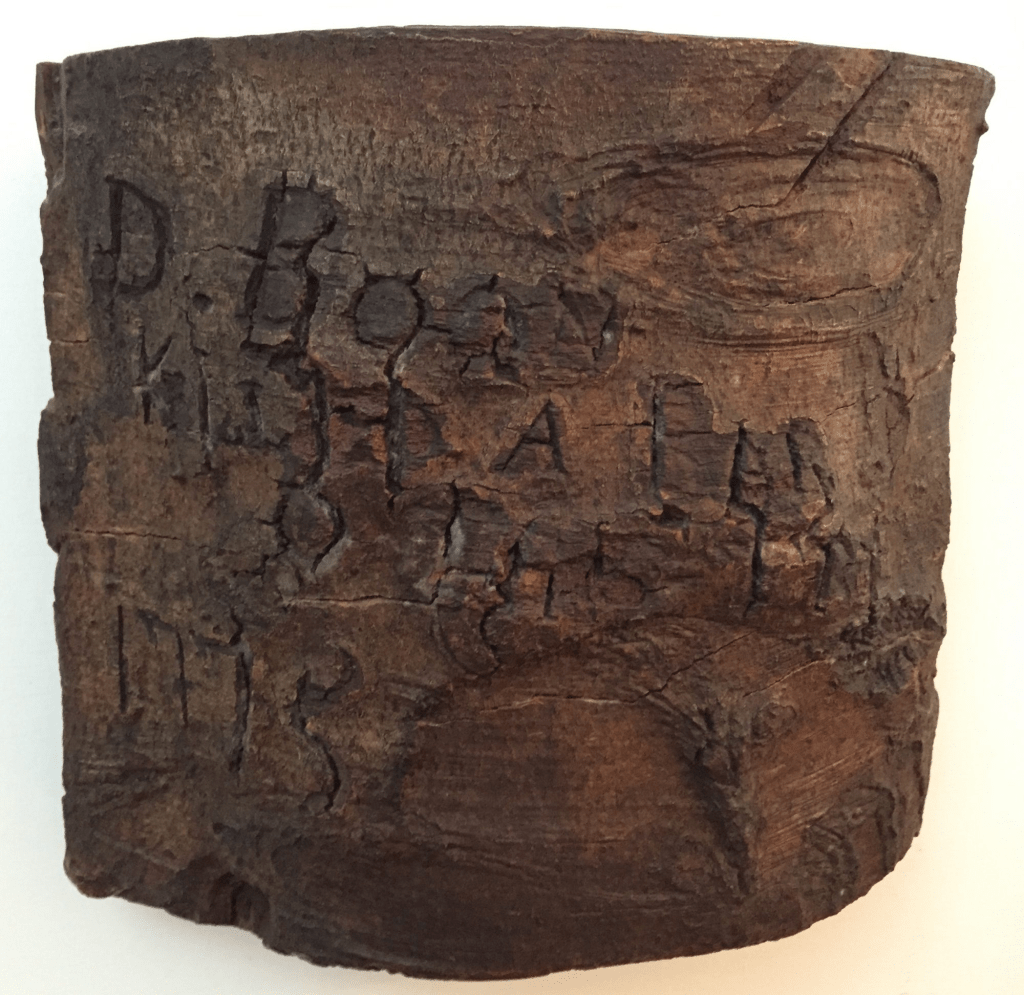

One of the prize possessions of the Preston family is the “Boone Block”—a segment of the trunk of a beech tree that bears the inscription:

D. Boon

Killd A Bar

O This Tre

1775

Family legend says that John M. Preston found this tree while riding over the farm (some stories even claim that the Boone Tree was the reason Preston wanted the property to begin with.) Not long after acquiring Exchange Place, Preston cut the tree down and preserved the portion bearing Boone’s inscription. This portion still hangs in the Preston-Stuart home (“The Bank”) in Abingdon today. A facsimile hangs in the Main House at Exchange Place.

It should be noted that Exchange Place operates independently of city, county, state, and federal governments. As part of the Netherland Inn Association, a privately funded nonprofit, it relies on committed volunteers who have acquired, relocated, preserved, and stewarded historic structures that would likely have been lost.

We owe them a great debt of gratitude.

Leave a comment