That’s a headline from the 1906 Chattanooga News. I’m fascinated with the period of history between the first Kingsport (1822) and the second one (1917). It started as a riverport but was left behind as commerce moved to railroads, and it had none. It’s often referenced as one of Tennessee’s “ancient” towns, but we only celebrated its 100th birthday in 2017. So, which is it? It’s both.

After Johnson City and Bristol rose as railroad towns with routes following the natural course of the Tennessee Valley, George L. Carter decided to build another railroad that rain against the grain. He planned to connect the Carolinas to Cincinnati and Chicago through the coalfields of Virginia and Kentucky. This gave Kingsport a second chance and formed the third anchor of what we know today as the Tri-Cities.

What the article calls the South & Western was George L. Carter’s construction-era company. Two years later (1908) it was reorganized as the Carolina, Clinchfield & Ohio (CC&O) and, from the 1920s onward, operated and popularly known as the Clinchfield Railroad—the very railroad most Kingsport folks remember.

That line also revived pieces of the earlier “3C” (Charleston, Cincinnati & Chicago) project. The 3C, headquartered in Johnson City in the late 1880s, faltered in the Panic of 1893 and was reorganized as the Ohio River & Charleston (OR&C). In the early 1900s Carter acquired key OR&C remnants and rights, folded them into his South & Western, and then resurveyed and rebuilt large stretches (keeping some roadbed near Johnson City) to create the modern, low-grade CC&O/Clinchfield main line.

In short: the 1906 story catches Kingsport at the moment the S&W was laying the groundwork for what soon became the Clinchfield, itself the successful successor to the unfinished 3C vision.

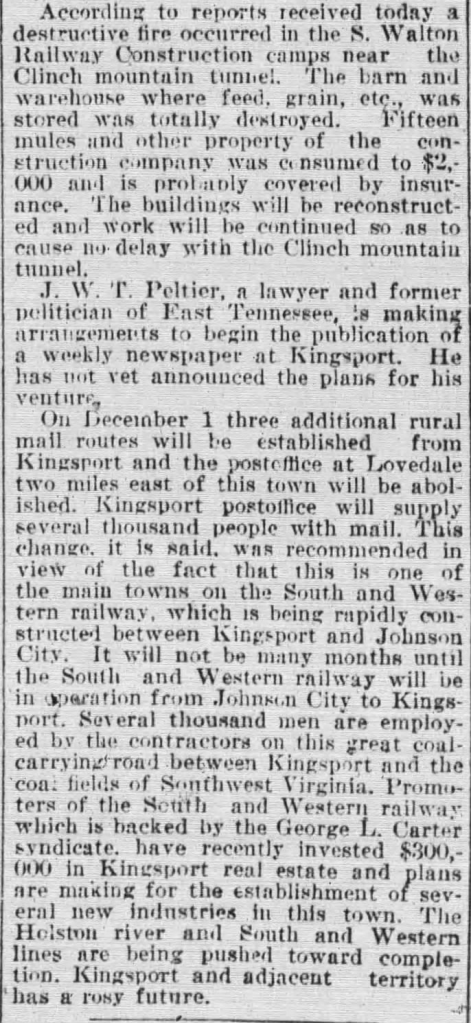

Transcript from the 1906 Chattanooga News…

“According to reports received today a destructive fire occurred in the S. W. Railway construction camps near the Clinch Mountain tunnel. The barn and warehouse where feed, grain, etc., was stored was totally destroyed. Fifteen mules and other property of the construction company was consumed to $2,000 and is probably covered by insurance. The buildings will be reconstructed, and work will be continued so as to cause no delay with the Clinch Mountain tunnel.

W. T. Peltier, a lawyer and former politician of East Tennessee, is making arrangements to begin the publication of a weekly newspaper at Kingsport. He has not yet announced the plans for his venture.

On December 1 three additional rural mail routes will be established from Kingsport and the postoffice at Lovedale two miles east of this town will be abolished. Kingsport postoffice will supply several thousand people with mail. This change, it is said, was recommended in view of the fact that this is one of the main towns on the South and Western railway, which is being rapidly constructed between Kingsport and Johnson City. It will not be many months until the South and Western railway will be in operation from Johnson City to Kingsport. Several thousand men are employed by the contractors on this great coal-carrying road between Kingsport and the coal fields of Southwest Virginia. Promoters of the South and Western railway, which is backed by the George L. Carter syndicate, have recently invested $300,000 in Kingsport real estate and plans are making for the establishment of several new industries in this town. The Holston River and South and Western bridges are being pushed toward completion. Kingsport and adjacent territory has a rosy future.”

Conclusion

George L. Carter (1857–1936) was the rail-and-coal entrepreneur behind the South & Western—reorganized as the Carolina, Clinchfield & Ohio and later known simply as the Clinchfield—whose vision set the stage for modern Kingsport. As construction advanced (local papers chronicled it mile by mile), he ran his corporate playbook from Bristol, moving Virginia Iron, Coal & Coke there and quietly backing the paper that became the Bristol Herald Courier. He made Johnson City his field base, donating land for the state normal school that became ETSU and laying out the Tree Streets alongside industrial projects like the Model Mill. In short, Bristol was Carter’s boardroom, Johnson City his field office, and Kingsport his industrial hub. He soon entrusted Kingsport to his brother-in-law J. Fred Johnson and his Kingsport Farms land holdings to James W. Dobyns. Carter also drew the New York house Blair & Company into the project, with John B. Dennis as its local partner. The butterfly effect of those early decisions attracted every early industry in Kingsport—including George Eastman—and still echo across the region. That brainpower was able to stabilize RDX at Holston Ordnance, the only non-nuclear explosive that could penetrate a German U-boat, and later the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge, which built the atomic bomb that ended World War II. At last count, 603,336 people call the immediate Tri-Cities home, an economy seeded by one man’s entrepreneurial vision.

Indeed, the future was rosy, just as predicted in 1906.

Leave a comment