Lately, I’ve been reading the book, “Franklin: America’s “Lost State” (Gerson, 1968). It’s a deep dive into the period of history of Americans residing west of the Appalachian Mountains from the end of the American Revolution in 1783 until 1791 when additional states beyond the original 13 were admitted to the union.

Virginia had long since indicated a willingness to cede its western lands for the future state of Kentucky, but the fledgling federal government was still getting organized, so it needed to prioritize things like adopting a constitution (1788) and a Bill of Rights (1791) first. With the knowledge that Virginia supported its eventual independence, the citizens were content.

The same could not be said, however, for what would eventually become Tennessee. The mother state of North Carolina had no intention of ceding its western lands and the state legislature reaffirmed the position over and over again.

Meanwhile, pioneers continued pouring across the mountains to places like Greeneville (1772), Jonesborough (1779), and Nashville (1779). They skipped places like Knoxville (1786) and Chattanooga (1816) because those lands were still dominated by the Cherokee.

The original settlers of Middle Tennessee famously departed today’s Kingsport in 1779. Donelson went by water, while Robertson went by land. The met at French Lick on the Cumberland River, today’s Nashville, Tennessee.

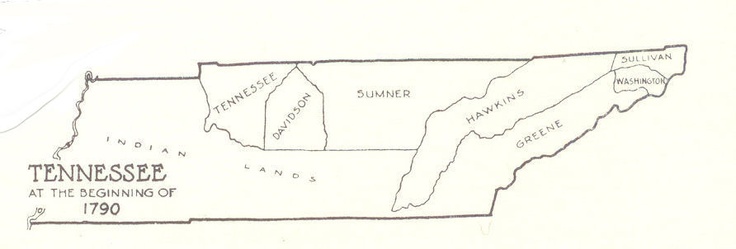

This also explains why today’s Tennessee counties that were originally incorporated in North Carolina are: Washington, Sullivan, Davidson, Greene, Hawkins, Sumner, and Tennessee (a county with the same name as the eventual state). Notice there’s no mention of Knox County, Hamilton County, or any county in between.

This created a sporadic development pattern for North Carolina’s western lands as there was a vast gap between Jonesborough, Greeneville, and Nashville–a distance of 250 miles.

In 1784, the settlers around Jonesborough & Greeneville formally met and declared themselves a new state called, “Franklin”. John Sevier was named the first ‘governor’. Of course, North Carolina did not concede, and it sparked years of bickering between the parent state and its defectors. The settlers around Nashville were content to remain in North Carolina and avoided getting in the middle of the conflict.

In 1787, however, Native American tribes threatened the remote city of Nashville. Colonel Robertson called for help from Governor Caswell of North Carolina. “Any troops North Carolina might dispatch to the town would, of necessity, be forced to march through the territory of Franklin (Northeast Tennessee). The sensitive Franklinites would probably believe they were being invaded by the parent state and civil war would almost certainly break out.”*

Colonel Robertson then turned to Kentucky, but it was busy with its own self-defense. “Nashville’s only hope was to turn to the Franklinites, whom they had spurned. Colonel Robertson swallowed his pride and wrote an urgent letter to Governor John Sevier.”*

“(Franklin’s) entire militia force was mobilized within 72 hours, a remarkable achievement at a time when word of mouth was the only means of communications.”*

“(Sevier) personally led the bulk of his own militia, more than two thousand strong, on a march through the forest wilderness towards the remote city of Nashville and her outlying settlements.”*

“(Sevier) and his men were greeted as heroes by the overjoyed residents of Nashville, who made it plain that they were disgusted with North Carolina.

And that’s how the first (Tennessee) volunteers–from the lost State of Franklin– saved Nashville.

Although Franklin failed as a state, it sowed the seeds that would eventually become the state of Tennessee and John Sevier would become its first governor as well.

The Lost State of Franklin made her mark as the first governors of both Kentucky & Tennessee hailed from the territory. Kentucky’s first governor, Isaac Shelby, hailed from today’s Bristol (1770), while Tennessee’s first governor, John Sevier, originally hailed from Carter’s Valley on the Holston River near Kingsport (1773). They bonded over the common cause of Franklin and remained close friends the rest of their lives.*

Today, numerous counties in Tennessee and Kentucky are named after famous pioneer families with historic ties to the lost state of Franklin: Sevier, Cocke, Campbell, Shelby, Carter, Robertson, Tipton, Boone and Crockett, to name a few.

*Franklin: America’s Lost State, Gerson, 1968

Leave a comment